It’s a damp rainy day when I visit artist Ayesha Sultana in Lilburn, Georgia. It’s been a difficult visit to schedule, with lengthy email chains and rescheduling, as it often seems to be the case in these post-lockdown years. In-person studio visits can feel like flexing a rusty muscle, and we are both relieved to see each other. Ayesha’s studio, located in the basement of her home, is pleasant, well-lit, and airy. The space is clean and ordered, but the wild paint splatters on the floors and walls reveal the ghosts of past exuberances.

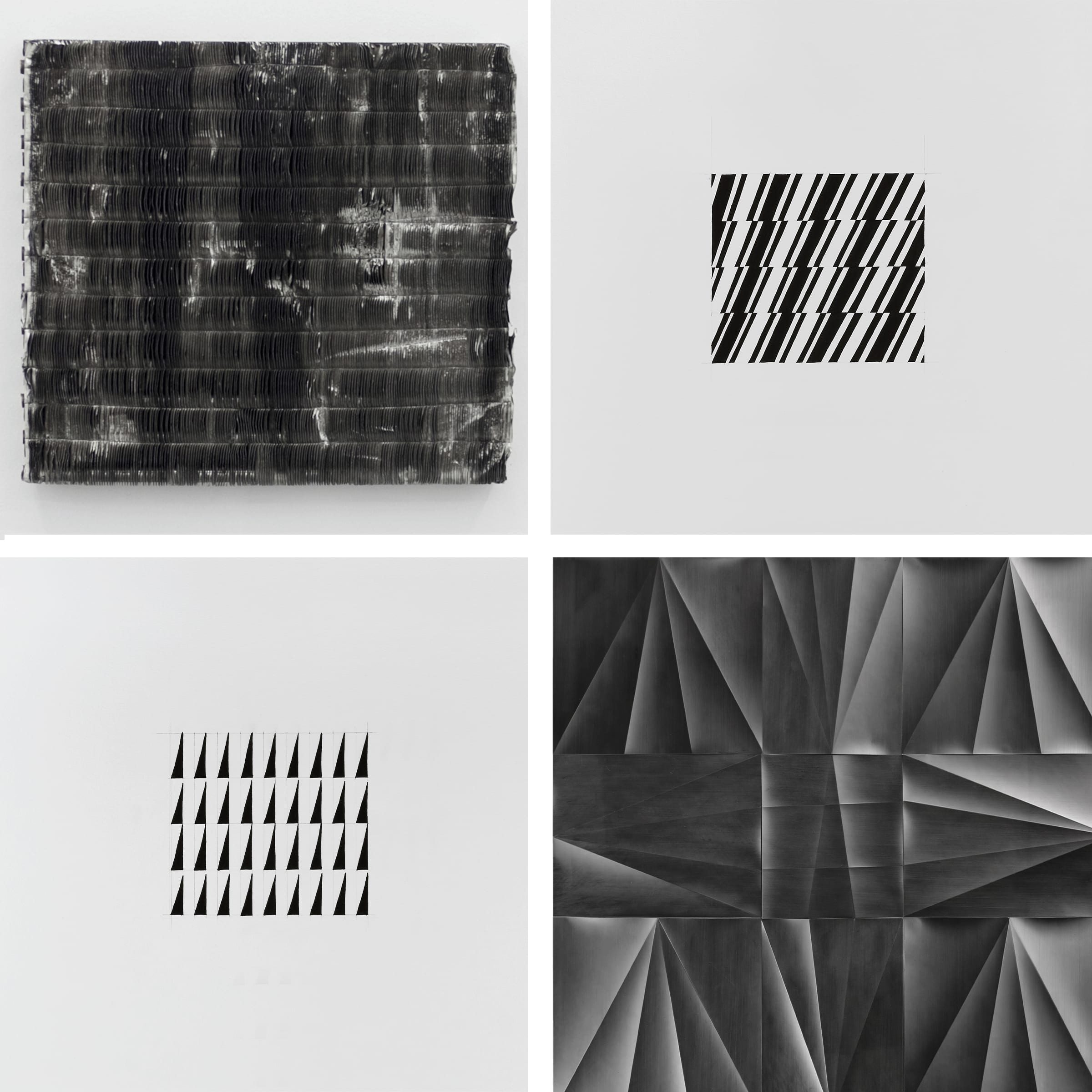

A few of Sultana’s graphite works, for which she is perhaps best recognized, were displayed partly assembled on a table by the window. For these works, Sultana plans the composition before treating the paper with three or four coats of graphite powder, with fixative between each layer – this, she says, tends to be the most arduous part of the process. She then applies pencil to paper, folds and bends the paper into repetitive shapes, and finally assembles all the pieces together to create an illusion of metal paneling. ‘Paper is such a versatile medium, just paper and pencil… it’s a very basic element that you’re using to create something that could transform into something else,’ Sultana says. Indeed, the works could easily be mistaken for metal or iron works. They are monochromatic, industrial, and ordered. When assembled on a large scale, as they often are, they appear particularly imposing.

Sultana might disagree with notions of an invisible hand. She points out the thumb and finger marks that inevitably appear when working with graphite, though to a casual viewer the smudges would be indiscernible. A curious phenomenon happens in the Lilburn studio that doesn’t occur when viewing the works on a screen, or even in a gallery setting. The gray-blue light of the recent storm comes through the studio windows and illuminates the graphite in a way that changes the appearance from hard and metallic to delicate and luminous. That moment, when light interacts with the materials, underlines Sultana’s exploration of contradictions. What is soft is made hard, what is light is made heavy, and back again.

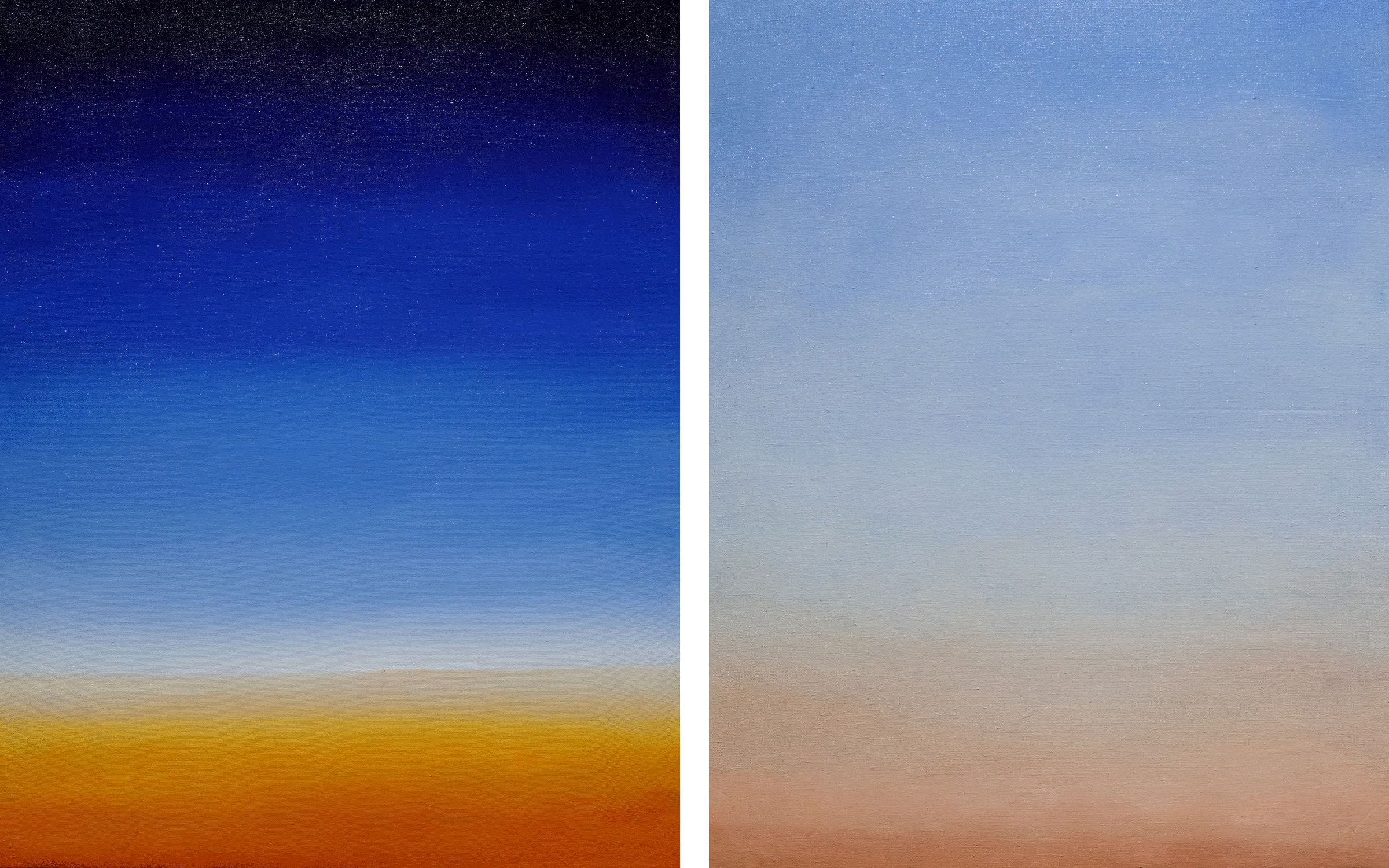

The common threads across Sultana’s practice are not immediately obvious. In addition to her graphite works, Sultana creates with a wide range of mediums, including oil paint, brass, iron, glass, tissue paper, aluminum, plaster, acrylic, and linen. Beyond diverse materials, she depicts a wide range of subject matter. Sultana’s paintings often consider the natural environment rather than the constructed one. While the graphite works are structured and monochrome, her paintings are colorful, blurry, emotional, and without a sharp line. Vibrant blues, reds, and oranges are layered upon the canvas in 4:04 (2021), a dreamy, abstract oil painting of a sunrise. In 12/21 (2021), bright green leafy fronds appear to sway in the wind against a light blue backdrop with loose and thick brushstrokes. Clouds billow, seas roll, and skies turn from black to blue to copper.

How are we to make sense of Sultana’s paintings in relation to their powerful, somber, geometric companions? If this is an artist interested in patterns, what patterns can be gleaned from such a divergent body of work? Perhaps by what they often lack: a human figure. Sultana’s environments, whether it’s ocean waves or a metallic wall, tend to be devoid of figuration. Minimalist form, shape, and light take center stage over depictions of the human form. However, that is not to say there isn’t an implied human presence. In Sultana’s sculptural graphite pieces, structures may refer to humanity’s capacity to build and create, conjuring questions of destruction via industry, capitalism, and environmental crisis. Cascading (2022) has the appearance of a long, checkered plate panel taken from a construction site –unyielding, man-made, and heavy –but in reality its materials are fragile and thin, perhaps alluding to the innate precariousness of global systems of power.

Sultana herself, as a creator, is also present in the work. ‘I feel like all the works are kind of autobiographical in some sense,’ the artist reveals. This presence can be subtle and intimate. In paintings like Under the waves (2022) and Sank in the burrows (2022), water takes on a deeper meaning. ‘The water for me is like feminine energy,’ she tells me. ‘It’s also about being fluid, and adapting to different situations.’ Sultana has a lot of experience in adaptation. Born in Bangladesh, she has lived, worked, and studied around the world, and exhibited in Kolkata, San Francisco, Mumbai, Rome, New Delhi, Dhaka, Paris, Vienna, and elsewhere. She has lived in overcrowded cities, and in Georgia suburbs, which explains why a consideration of place is consistently a theme. But Sultana does more than simply draw inspiration from her surroundings. She enacts a case study in place and structure. In her series ‘Form Studies’ (2017-2018), Sultana breaks down elements of her surroundings, such as the view of a staircase from her studio window, into abstract drawings. The studies are taken a step further when Sultana reinterprets them as three-dimensional sculptures, another layer of abstraction.

While the places depicted in her work are unique and personal to her, to an audience they may take on a placelessness. This liminality is at once alienating and universal, and open to interpretation; much like Sultana’s practice. Sultana’s environment, like her work, frequently exists in a state of evolution and flux, and yet her approach is methodical and thoughtful. Marks are scratched onto clay-coated paper in time with the artist’s breathing in her series ‘Breath Count’ (2019 – present), which now consists of over 100 pieces. ‘It’s a process of subtraction,’ says Sultana, in contrast to her paintings and drawings that hinge on layering and addition.

Creating ‘Breath Counts’ is a meditative, intentional process, and the results feel deeply personal. The artist becomes an element in each composition, their presence becoming legible on the page through the documenting of time and the act of repetition, which both define Sultana’s practice. In the large-scale graphite works, such as Scrim (2022), many small sheets of paper have been folded individually to create the illusion of metallic plating. This process of treating the paper, applying graphite, and assembling into the final installation, is tedious and labor-intensive. But that is not to say it is unpleasant. ‘I like to build up work on the surface,’ says Sultana. ‘Whether it’s with thin coats of paint or preparing the surface of the materials, whether its paper or linen, building it over time.’

Absence creates presence, sometimes in a literal sense. On photographing graphite on paper, Sultana notes: ‘If you’re standing in front of it, you see an outline of the photographer. You become part of the work.’ Thus, while Sultana describes her practice as autobiographical, what emerges across her works is both a portrait of a multifaceted artist, who thoughtfully breaks the world around us down into the basics –shape, form, light, and color – and an expansive landscape of worldly reflections. For those of us who look at the results, we might find ourselves silhouetted among the pieces.

Ayesha Sultana is represented by Experimenter (Kolkata, Mumbai). Her work is currently on view as part of Artist’s Rooms at Jameel Art Centre, Dubai, from November 10, 2022 to May 14, 2023.

EC Flamming is a writer and editor based in Atlanta, Georgia. Her work focuses on the cultural impacts of moving images and contemporary art to explore how media consumption shapes and reflects social relations. She has written for ART PAPERS, ArtsATL, Paste, BURNAWAY, Photograph, and Another Gaze.

Published on Febuary 3, 2023.

Caption for full-bleed images: 1. Ayesha Sultana’s studio. Photograph by Peyton Fulford for Art Basel. 2, 3 and 4. Ayesha Sultana in her studio. Photography by Peyton Fulford for Art Basel. 5. Ayesha Sultana, Scrim, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Experimenter (Kolkata, Mumbai).