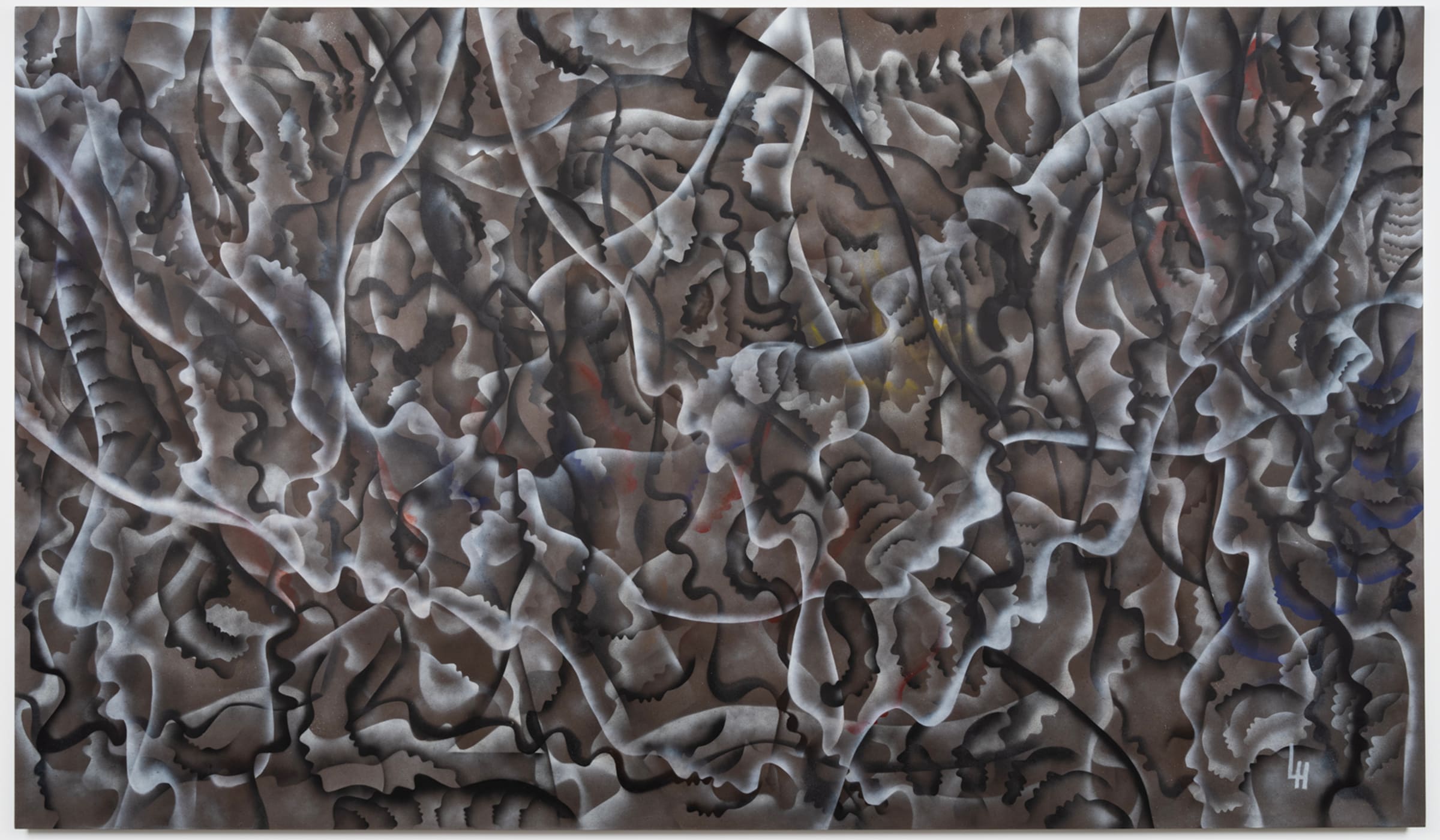

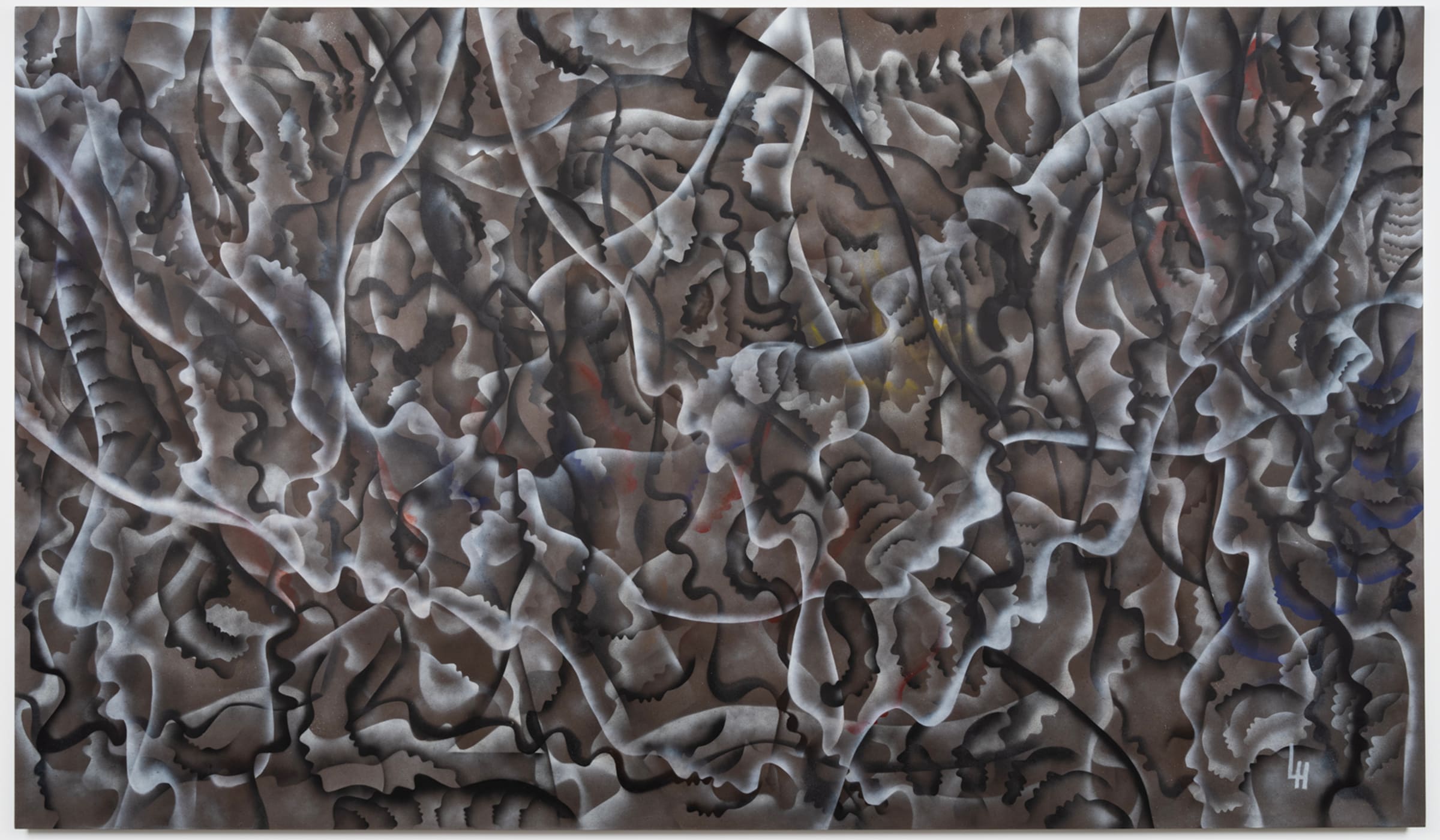

Lonnie Holley, We Are the Fruits of Their Labor, 2022. Photograph by Sai Tripathi. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe.

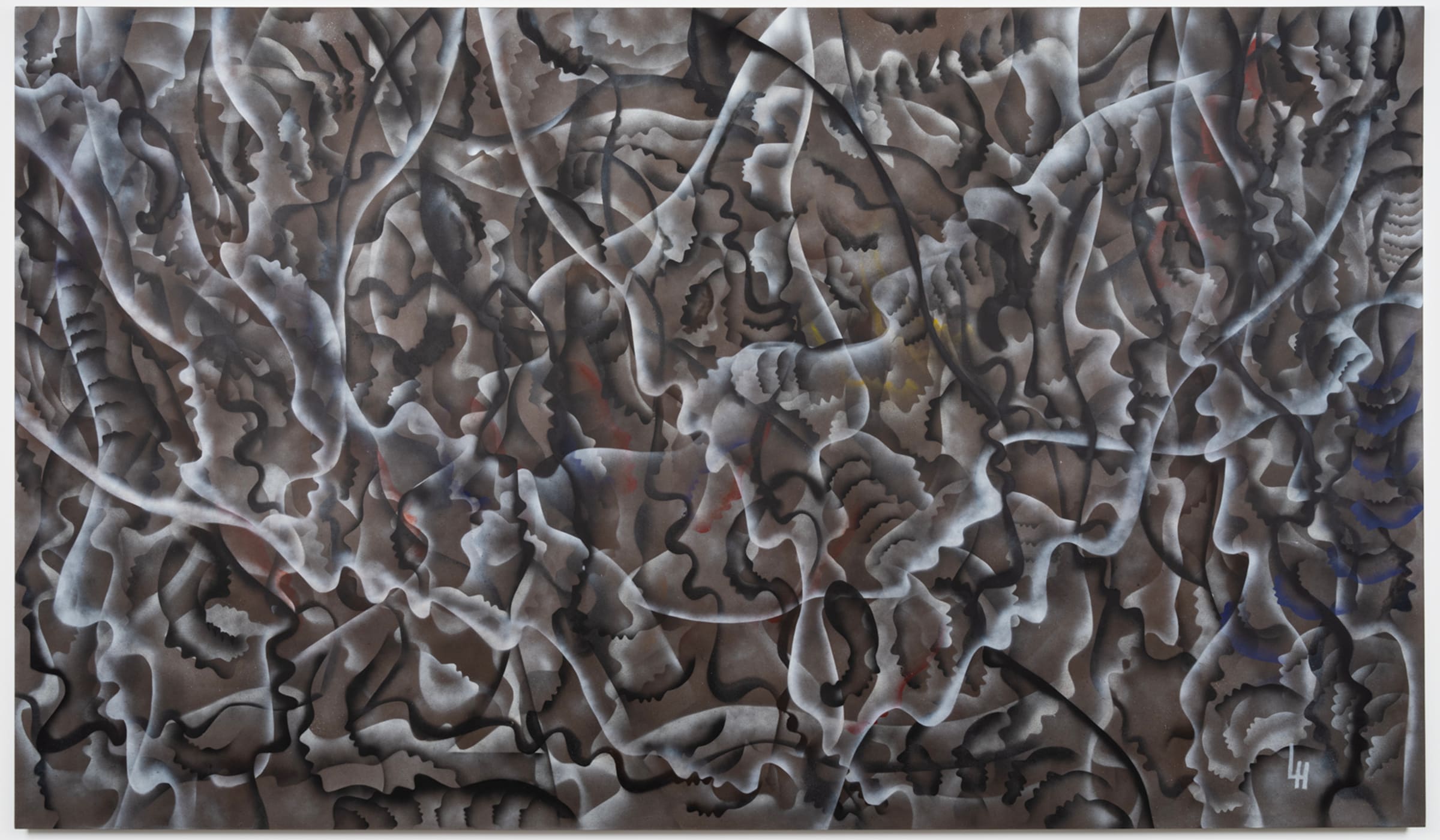

Lonnie Holley, We Are the Fruits of Their Labor, 2022. Photograph by Sai Tripathi. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe. Lonnie Holley, Adding to the Foundation (Honoring Daddy James), 2021. Photograph by Josh Schaedel. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe.

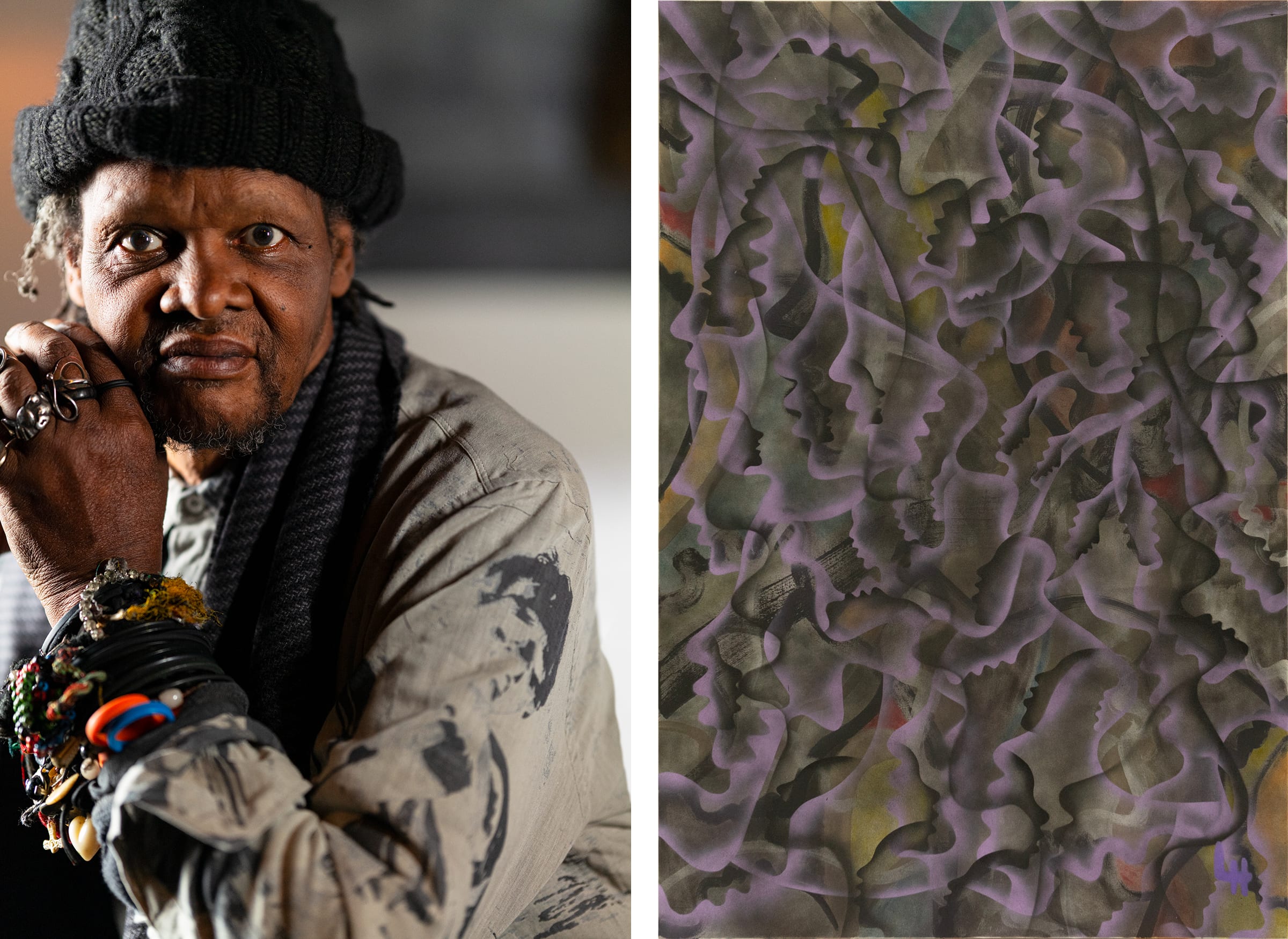

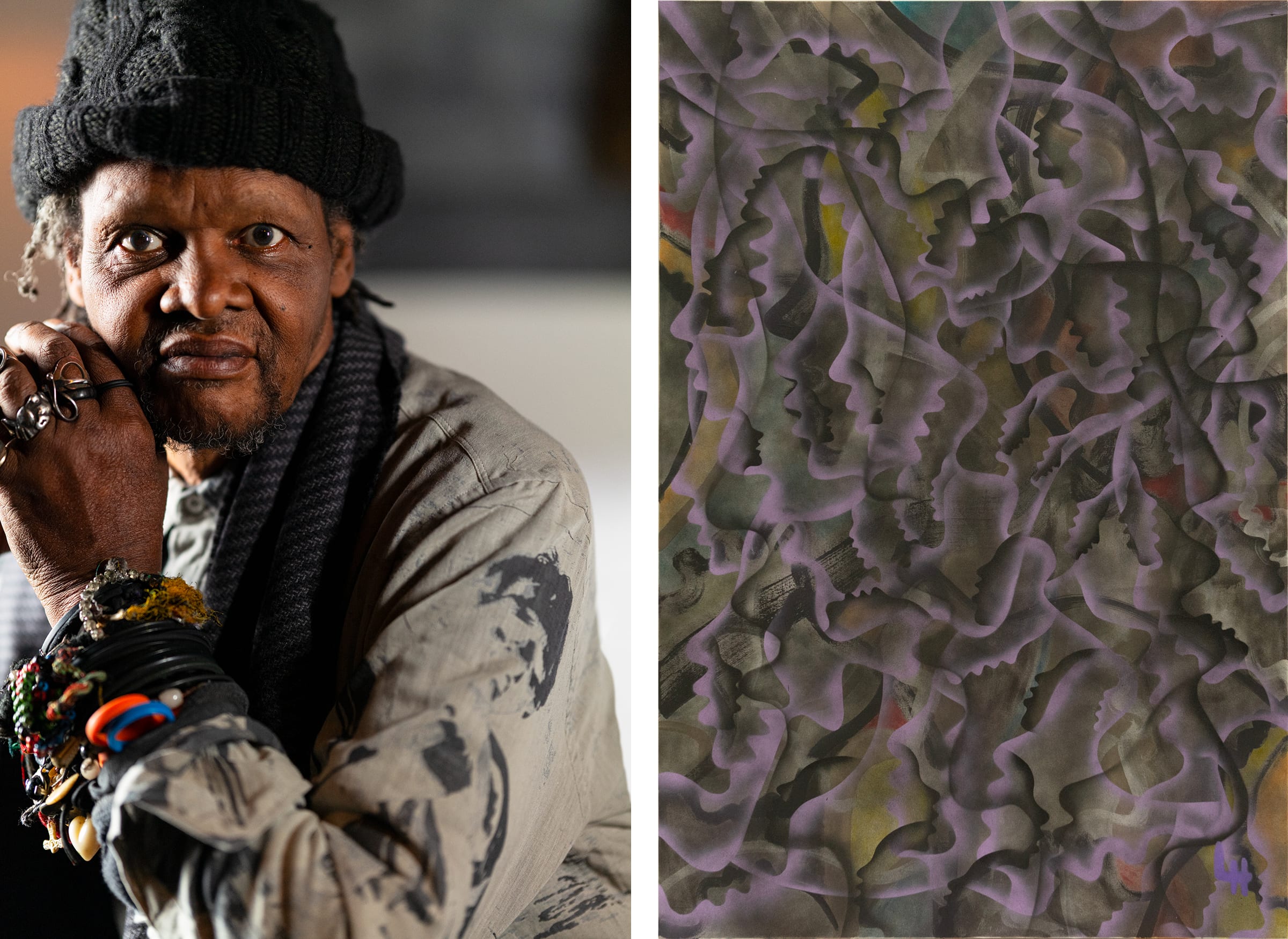

Lonnie Holley, Adding to the Foundation (Honoring Daddy James), 2021. Photograph by Josh Schaedel. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe. Left: Lonnie Holley. Photograph by David Raccuglia. Right: Lonnie Holley, The Light at the End of Our Darkness, 2023. Photograph by Truett Dietz. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe.

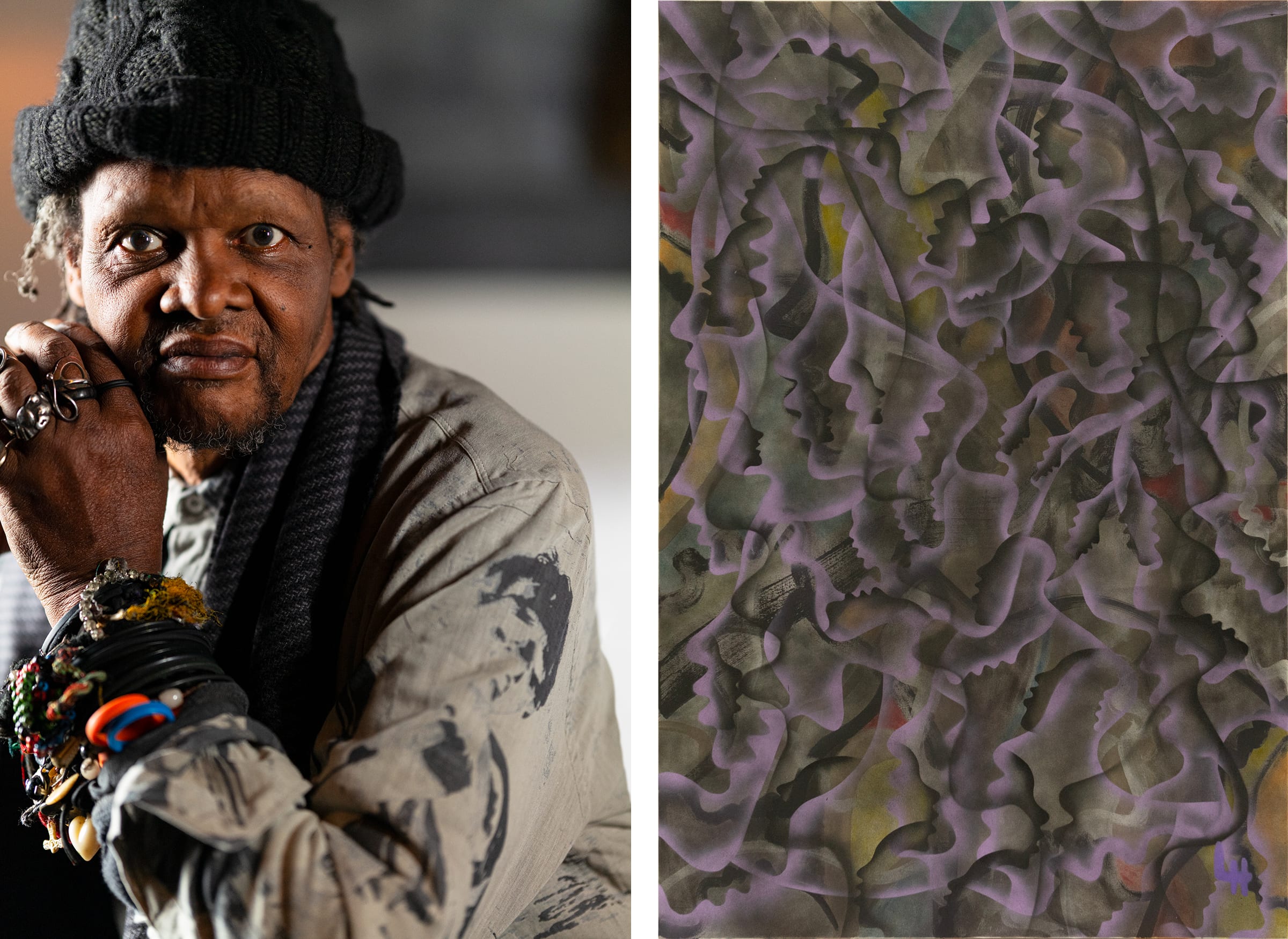

Left: Lonnie Holley. Photograph by David Raccuglia. Right: Lonnie Holley, The Light at the End of Our Darkness, 2023. Photograph by Truett Dietz. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe. Left: Lonnie Holley, Untitled, 2021. Right: After the Mutiny, 2021. Photographs by Josh Schaedel. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe.

Left: Lonnie Holley, Untitled, 2021. Right: After the Mutiny, 2021. Photographs by Josh Schaedel. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe. Left: Space Babies Will See the Flag Upside Down, 2008. Josh Schaedel. Right: Trapped (for Ronald Lockett), 2019. Photographs by Josh Schaedel. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe.

Left: Space Babies Will See the Flag Upside Down, 2008. Josh Schaedel. Right: Trapped (for Ronald Lockett), 2019. Photographs by Josh Schaedel. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe. Lonnie Holley. Photograph by David Raccuglia. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York,. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe.

Lonnie Holley. Photograph by David Raccuglia. © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York,. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe.