In 1958, Allan Kaprow wrote, ‘We must become preoccupied with and even dazzled by the space and objects of our everyday life.’ Following his words, the collective, We Do Not Work Alone (WDNWA), pursues the blurring of boundaries between art and life. Founded in 2015 by Louise Grislain, Anna Klossowski, and Charlotte Morel, WDNWA works with contemporary artists to design and produce limited editions of inexpensive, usable objects.

The collaborators first met and became friends in 2008 while attending the curatorial studies master’s program at the Sorbonne in Paris. After graduating, they started organizing shows together in artist-run spaces under the name KGM, an acronym of their initials, which as Grislain remarks ‘we thought was funny because it sounded a bit like the name of an insurance company or something like that.’ Their approach however has always been far from corporate. In fact, after several years of working at commercial galleries as their day jobs, the three women began discussing alternative structures. ‘At the time, all of our friends were artists,’ Klossowski recounts, ‘and they were saying to us “start a gallery, start a gallery!”, but we thought this will surely end up with everyone getting fed up with each other.’ Noticing that many of their artist-friends were crafting useful objects and making household items by hand, they started to think about a business format dedicated to such projects. They named their new venture after a 1953 book by Japanese potter Kawai Kanjiro, for they felt the title perfectly captured their mission. Thus, the three friends formed WDNWA, and set out to create a model that would give priority to collaboration, dialogue, and above all, forging close relationships with artists.

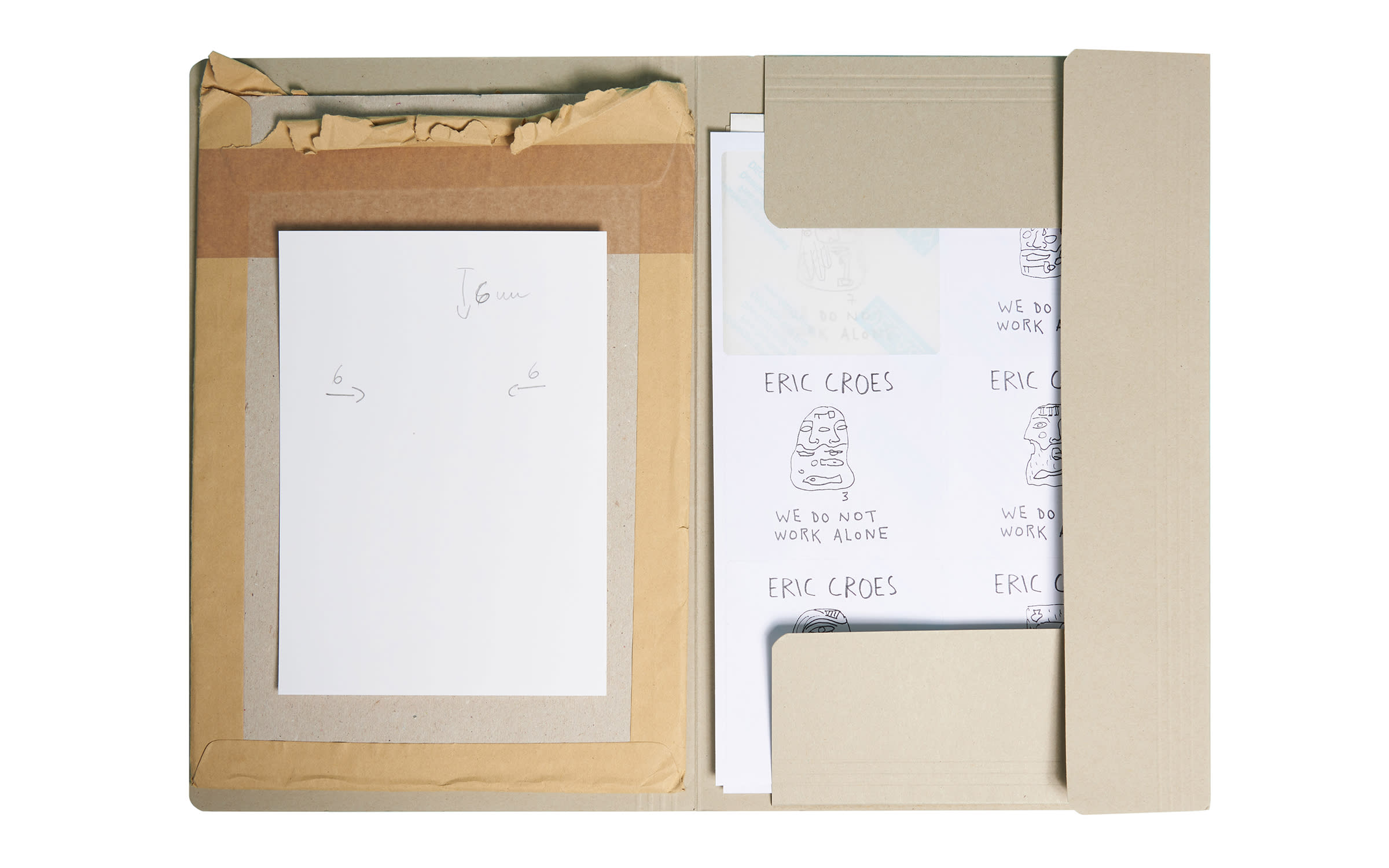

For their first venture into business, WDNWA signed up to participate in a contemporary art fair devoted to editions. With only three months to prepare, they asked six artist-friends to design objects. The resulting items included a ceramic soap dish in the shape of a grotto by Florian Bézu, enameled porcelain buttons by Sophie Lamm, pétanque balls by Renaud Perriches, and lacerated canvas cushion covers – or as Klossowski describes them ‘Fontanas for your couch!’ – by Camila Oliveira Fairclough. After this first launch proved promising, WDNWA produced an edition by Mathieu Mercier: a pair of white handling gloves – one with the word ‘love’ and the other with ‘hate’, in reference to Robert Mitchum’s tattooed hands in the film Night of the Hunter (1955).

Since then, WDNWA has worked with more than 30 artists of varying ages and nationalities. They have produced objects such as a tablecloth by Olaf Breuning, a kitchen apron by Marc Camille Chaimowicz, a bath towel by Nina Childress, a pencil sharpener by François Curlet, a tape measure by Annette Messager, and a butter dish by Erwin Wurm. The creative process differs greatly from project to project, but it always entails in-depth conversation. Some artists start off with vague ideas and desires, and WDNWA helps them find a form and a material. Others have a precise idea for an object from the beginning, and WDNWA figures out a way to realize it. Through these exchanges, the artists end up creating objects they never would have made within their regular artistic practices. The importance of cultivating close relationships with the artists (as well as with the artisans and manufacturers) goes hand in hand with the type of objects produced by the collective. ‘Contemporary art can be very intimidating,’ Klossowski states, ‘You have to be respectful of a piece of art hanging on the wall, but we want to be able to hold art, to touch it, and use it.’ Grislain adds, ‘We believe that art is something that we need every day in order to live.’ Their hope is to show that collectors can relate to art in more personal ways.

Another chief concern for WDNWA is maintaining a sustainable economic model. ‘From the start, it was very important for us to be able to pay everyone, even if it was not a lot of money,’ Klossowski declares. She continues, ‘It seems obvious, but the reality is that for so long in the artworld many curators, writers, and artists have worked for free. We wanted to find another way to create – even if it was on a small scale – a system that everyone could benefit from.’ Keeping their prices as affordable as possible, WDNWA’s editions range from 18 to 5,000 euros. Moreover, true to their democratic principles, they determine the price of each object according to its production cost and never in relation to the financial success or prestige of the artist.

Last year, WDNWA opened its first permanent space. Located in the Marais in Paris, it functions as an exhibition space, a site to launch editions, a shop, and an office. However, the women consider this just one of their venues, and they emphasize their passion for making editions on different scales for different contexts. In the future, they hope to make their most affordable objects even more accessible and fantasize about selling them in supermarkets and airports.

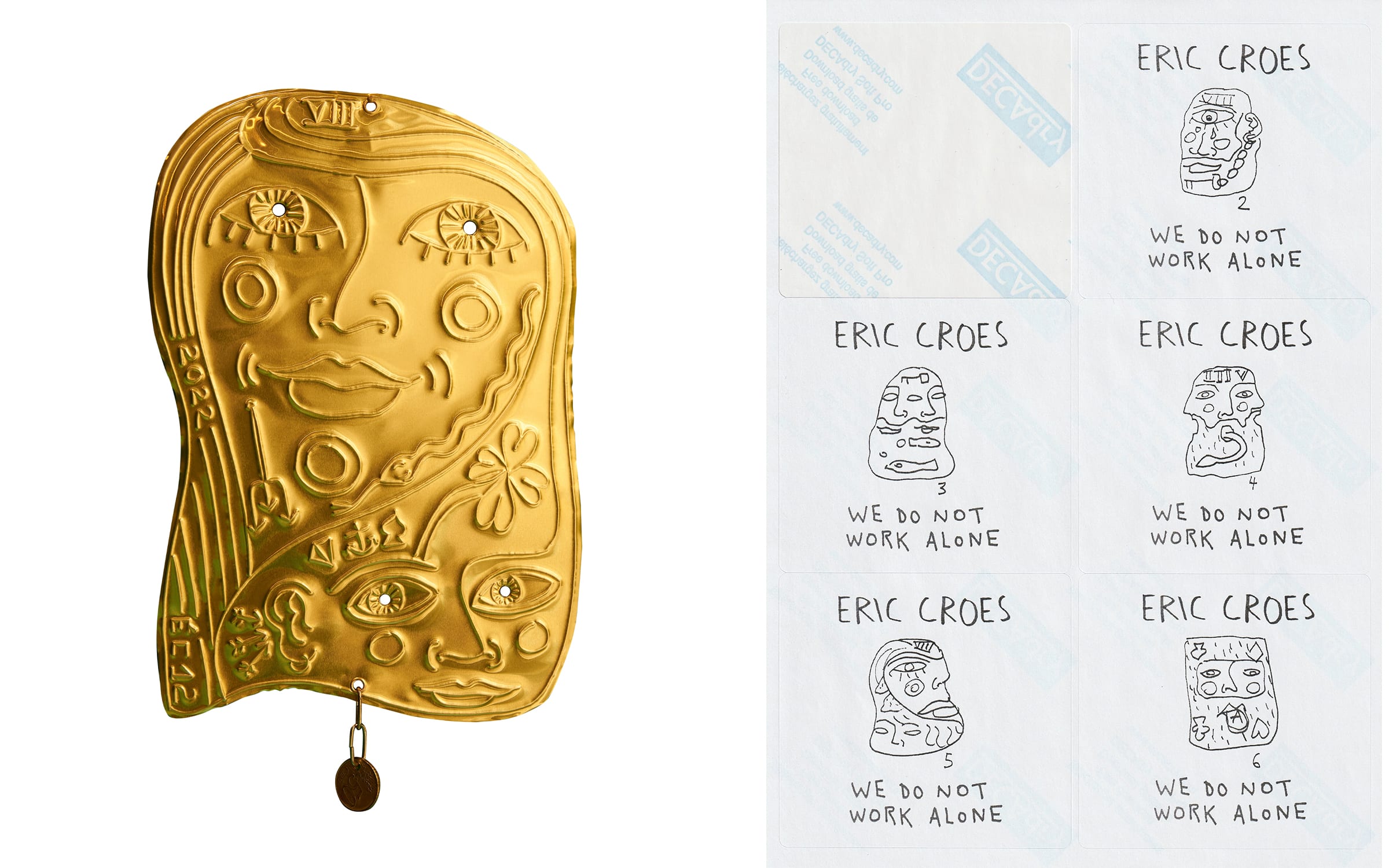

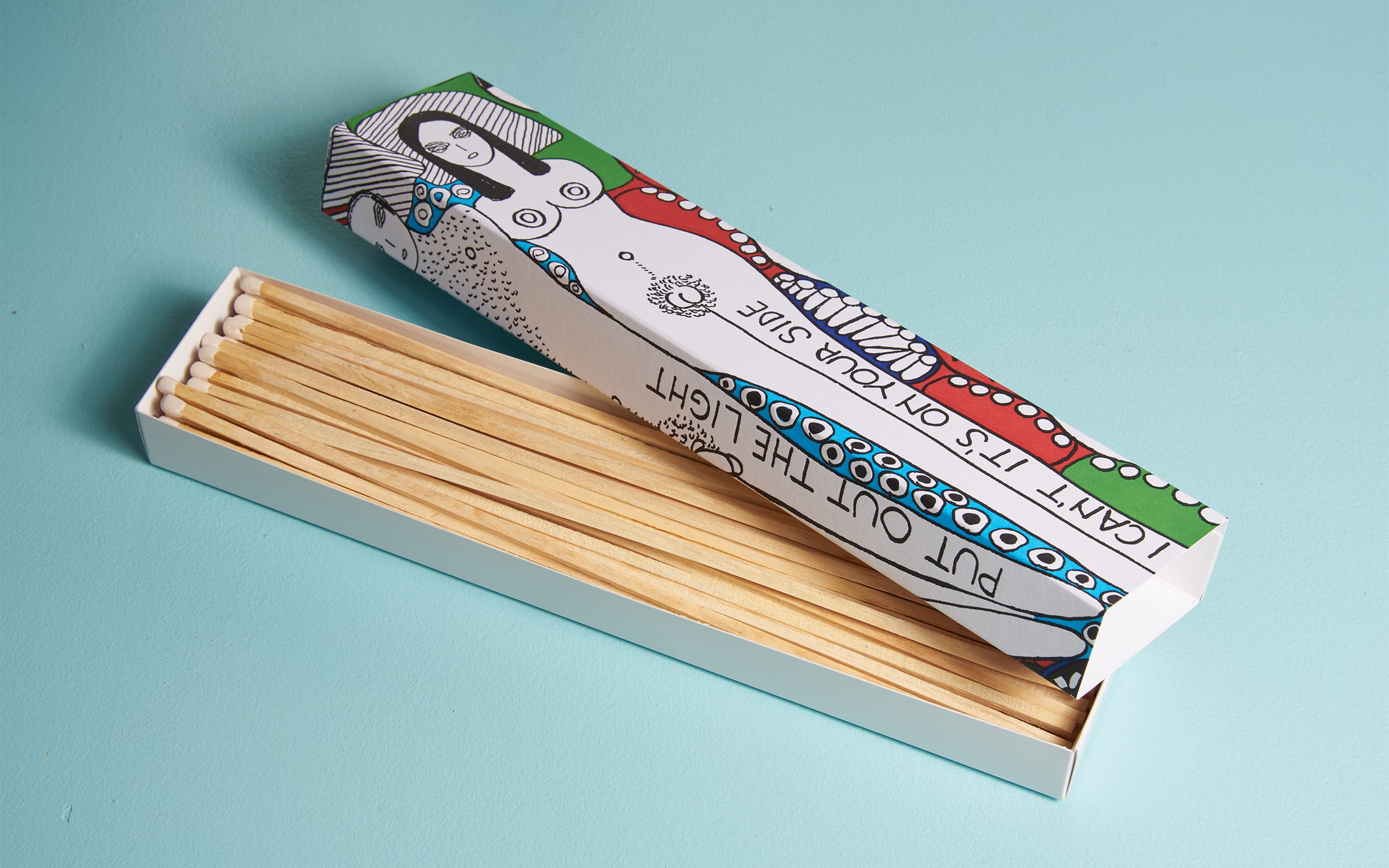

At Paris+ par Art Basel they plan to launch their most ambitious editions to date. They will present Poum-poum, tic-tac, plouf (2022) by Ryan Gander, a machined stainless-steel replica of Gander’s watch. It doesn’t work and plays on the fact that we no longer need watches because we look at our cell phones to check the time. While WDNWA usually sticks to a strict policy of producing usable objects, Gander found a loophole by arguing that its use is its uselessness. Klossowski explains, ‘this will be our first object with a symbolic function.’ They will also exhibit a collection of furniture entitled Light My Fire by pioneering artist Dorothy Iannone, based on a series of drawings she made in the 1960s. ‘This is the first time anyone has produced an edition of her furniture, so it’s historical work realized now,’ Grislain says excitedly. In addition, the booth will feature a metal table with a tiled top by Matthew Lutz-Kinoy. Its metal legs pay homage to a table by British potter Bernard Leach, and the painted ceramic tiles combine references to traditional Japanese craft. Since Lutz-Kinoy hand-painted all of the tiles, each table in this edition of 30 will be unique. Finally, for Bras de fer (French for arm wrestling), Eric Croes designed a bronze hammer in the shape of an arm holding a hammer. He also made a unique ceramic base that resembles an arm. So, in a clever mise en abyme, an arm holds a hammer, holding an arm, holding another hammer, and one can hold this hammer/art object to hang other art objects or maybe even other hammers?! The divergent meanings of Croes’ piece attest to the radical heterogeneity of this world, enabling the linkage of aesthetics and utility. To be sure, this object, as with all of WDNWA’s editions, affirms the potential of joining art and the everyday together.

Dr. Zoe Stillpass is a writer, curator, and professor based in Paris.

We Do Not Work Alone will participate in the Galeries sector of Paris+ par Art Basel, from Thursday, October 20 to Sunday, October 23, 2022.

Captions for full-bleed images:

Anna Klossowski demonstrating Dorothy Iannone's Light My Fire. Video by Mina Albespy for Paris+ par Art Basel.

Installation view of Eric Croes' exhibition ‘Bras de Fer’, We Do Not Work Alone, Paris, 2022. Photograph by Mina Albespy for Paris+ par Art Basel.

We Do Not Work Alone, Paris, 2022. Photograph by Mina Albespy for Paris+ par Art Basel.