‘Every time there’s an uptick in an art scene – like you’re seeing now in Saudi, and like you saw in China 20 years ago – there are artists who are important both for their work and also for the convening power that they have,’ says Philip Tinari, the director of the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing and Shanghai – and the curator of Mater’s first institutional retrospective. ‘That’s been Ahmed Mater. His studio has been a place to converge; he’s been a conduit for ideas; he’s been a node of connection.’

Since the early 2000s, Mater has been pivotal to the Saudi art scene. He got his start as part of the Shatta collective, with four other artists and poets, at Al Muftaha Art Village in his home province of Asir in the south of Saudi Arabia. Then, with Abdulnasser Gharem, Stephen Stapleton, and Ashraf Fayadh, he formed Edge of Arabia, which toured Saudi contemporary art abroad and challenged assumptions about the lack of art in the kingdom. Back in Jeddah, Mater set up Pharan Studio, which in the absence of an infrastructural system in Saudi played a crucial role as a space for lectures, discussions, and exhibitions. Now based in JAX, the new cultural district outside of Riyadh, his studio continues to bring together different creative practitioners, hosting graphic designers, musicians, artists, and visitors passing through to collaborate or simply discuss art and ideas.

‘As much as I give to community, that’s as much as I gain,’ says Mater. ‘I believe in the concept of open education – and from it I learn and get more energy to continue. Everyone shares with me their questions and it opens my mind to research more.’

Mater’s presentation at Art Basel Qatar, ‘Temporal Migration’, builds on the research he has conducted over the past decade into the economic and social shifts that his country has experienced. The photographs and prints are drawn from ‘Desert of Pharan’, an important body of work that he conducted in the mid-2010s when the holy city of Mecca was undergoing large-scale real-estate development to accommodate the growing number of pilgrims coming through. Mater’s photographs emphasize the intense social dimension of Hajj and Umrah (the two holy pilgrimages in Islam), as well as the uneasy relationship between the city’s sacredness and the money involved in its redevelopment. Ten years later, Mater is posing this moment as one of the earliest points in Saudi Arabia’s shift towards neoliberalism, which forms the core of his current project of ‘KPI.art’.

‘All of Ahmed’s work reflects a deep understanding of history, but also a kind of quiet activism that defines a lot of Saudi art,’ says Alia Al-Senussi, a senior advisor to the Saudi Ministry of Culture as well as Art Basel – and the co-author of Art in Saudi Arabia: A New Creative Economy? (2023). ‘Many Saudi artists, for so long, would comment on things that they wanted to see changed. So much of Vision 2030 – and so much of the incredible socioeconomic, sociocultural reforms we see being instituted – was inspired by people like Ahmed: by artists and cultural thinkers who understood from a deep sense of patriotism what they wanted, and then translated that into works of art.’

With the centrality of Mater to the narrative of the Saudi cultural sector, it is sometimes easy to overlook the precision and coherence of his artistic practice. In part this is also because of its breadth: it spans photography, installation, publications, found objects, and land art. (As well as his convening: Al-Senussi suggests that we think of his passion for the perfect coffee brew as an extension of his art practice.) In addition to his well-known responsiveness to the sociopolitical shifts around him, a crucial and enduring facet of his work is its connection to science. Mater trained as a doctor, and some of his earliest works – such as the now iconic series of X-ray works where a figure pointing a gun to his head morphs into a petrol pump (Evolution of Man, 2010) – were made from hospital materials, in part, simply because art production material was so difficult to find.

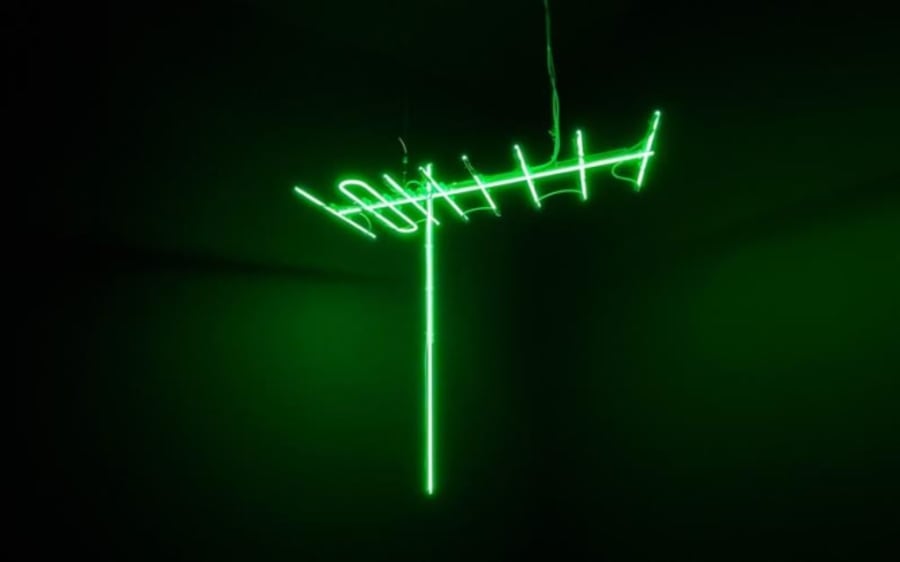

As he moved away from medicine, Mater’s interest in science remained. His most famous series, ‘Magnetism’, in which iron filings bend towards a Kaaba-like magnet set in the center of the frame, is often read as a religious allegory evoking Islam’s most sacred site, but it showcases the forces of magnetism, invisible to the naked eye. A later series of works investigated lightning, including Tesla Coil (2017), Lightning Land (2017), and Mitochondria: Powerhouses (2021), in which Mater installed a Tesla coil to recreate the extraordinary process in which energy takes a bright, jagged shape and appears out of nowhere to extend to the ground. The forthcoming Ashab Al-Lal – a vast installation of mirrors and bent light waves that will create holograms in the AlUla desert – will be a technical masterpiece when it is finally unveiled. Magnetism, tricks of perception, the idea of light bending or sparking into flame are all magical, incredible things that happen on a daily basis. Mater makes the processes of science, so often overlooked, the key focus of his joyful work. ‘Mater,’ Al-Senussi reminds us, ‘is a polymath.’

Mater’s interest in science also reflects the different positioning of scientific thought in an Arab and Islamic context, where it has historically sat close to philosophy. The 10th-century figure Ibn al-Haytham, for example, is considered both the father of the science of optics and a poet and theologian. Mater’s reprise of that role reflects both the freedom with which he works – ignoring the typical guardrails around contemporary art – as well as his fierce commitment to protecting what is different within an Arab and Islamic context. Indeed, one of the themes of his work, and visible throughout ‘Temporal Migration’, is a resistance to the uniformity that neoliberalism imposes on the world, with its reduction of culture to quantifiable metrics. Another element of Mater’s research into Mecca’s development is his 100 Found Objects (2014) and Mecca Windows (2013). (The latter work was recently installed in spectacular fashion at the UCCA Edge in Shanghai.) These works derive from Mater’s travels around the city under construction, rescuing everyday items and panels of the stained-glass windows that had been part of the city’s architectural vernacular – a Saudi specificity that was being lost in the transformation to luxury modernity.

And, in the way that everything comes full circle, his work as a cultural figure is also part of this mode of recuperation and safeguarding. He recently opened the Ahmed Mater Foundation, a stone’s throw from Al Muftaha Art Village, where he studied in the 1990s. His plans for the foundation are to create a similar space for experimentation to the one that he enjoyed there – bringing back the freedom that he feels is now curtailed.

‘There was no art world when we started,’ he recalls. ‘Either you wanted to be an artist or not. There was no market, no exhibition, no museum. Just artists creating artwork. And that’s a great thing, to work far away from the art glory. I want to bring that back.’

Ahmed Mater is presented at Art Basel Qatar, February 7 to 8, 2026, by Athr Gallery. The artist will host a meet and greet and sign posters at the Art Basel Shop (M7 - Msheireb Cultural Centre) on Friday, February 5, from 12:30 to 1pm. Discover more.

Melissa Gronlund is a writer based in London. Her work has appeared in titles including e-flux; Afterall; Artforum; BBC; The London Review of Books; Financial Times; and The Guardian. She was the chief art correspondent for The National in Abu Dhabi from 2017 to 2019.

Caption for header image: Dr. Ahmed Mater, Black Stone, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Athr Gallery.