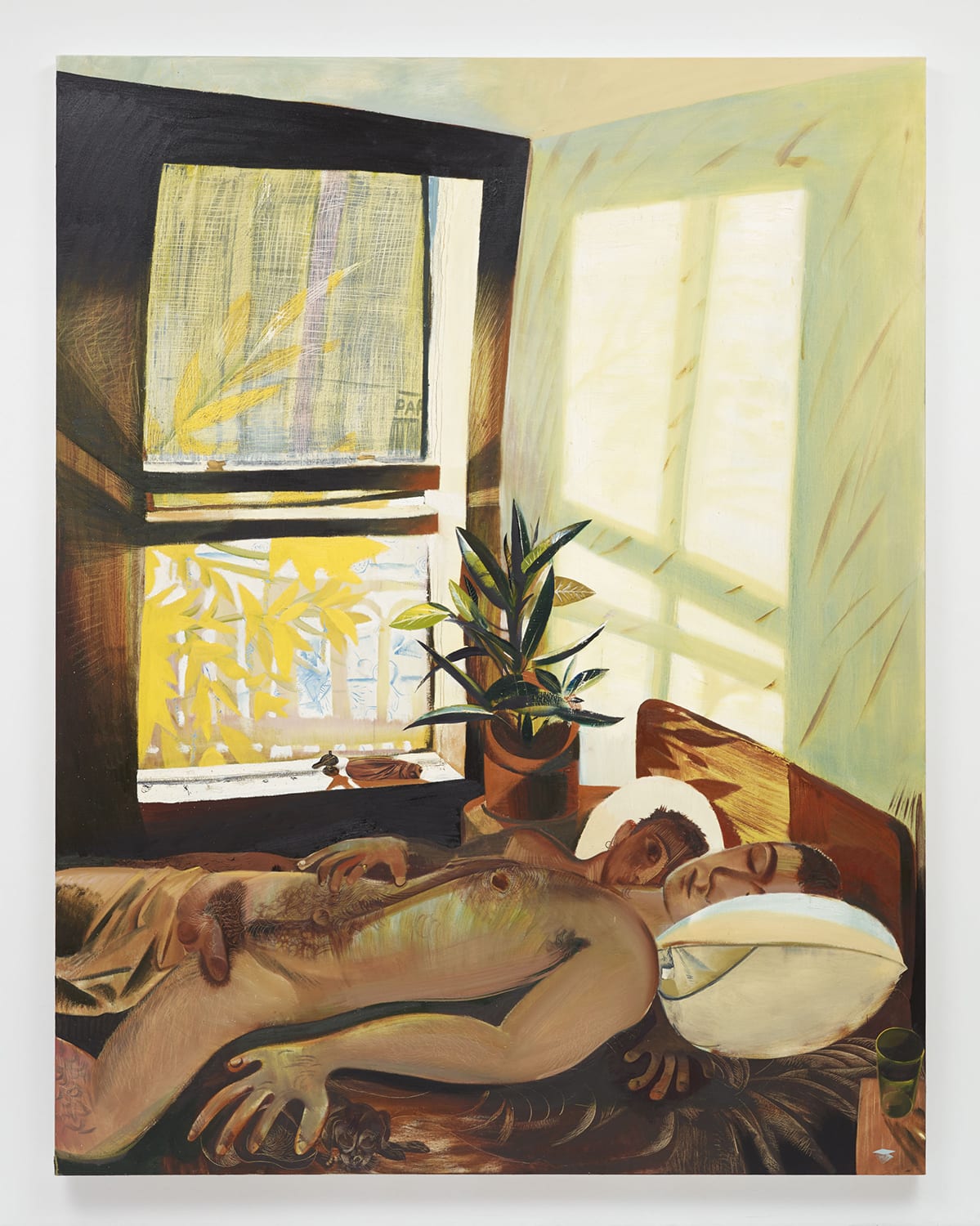

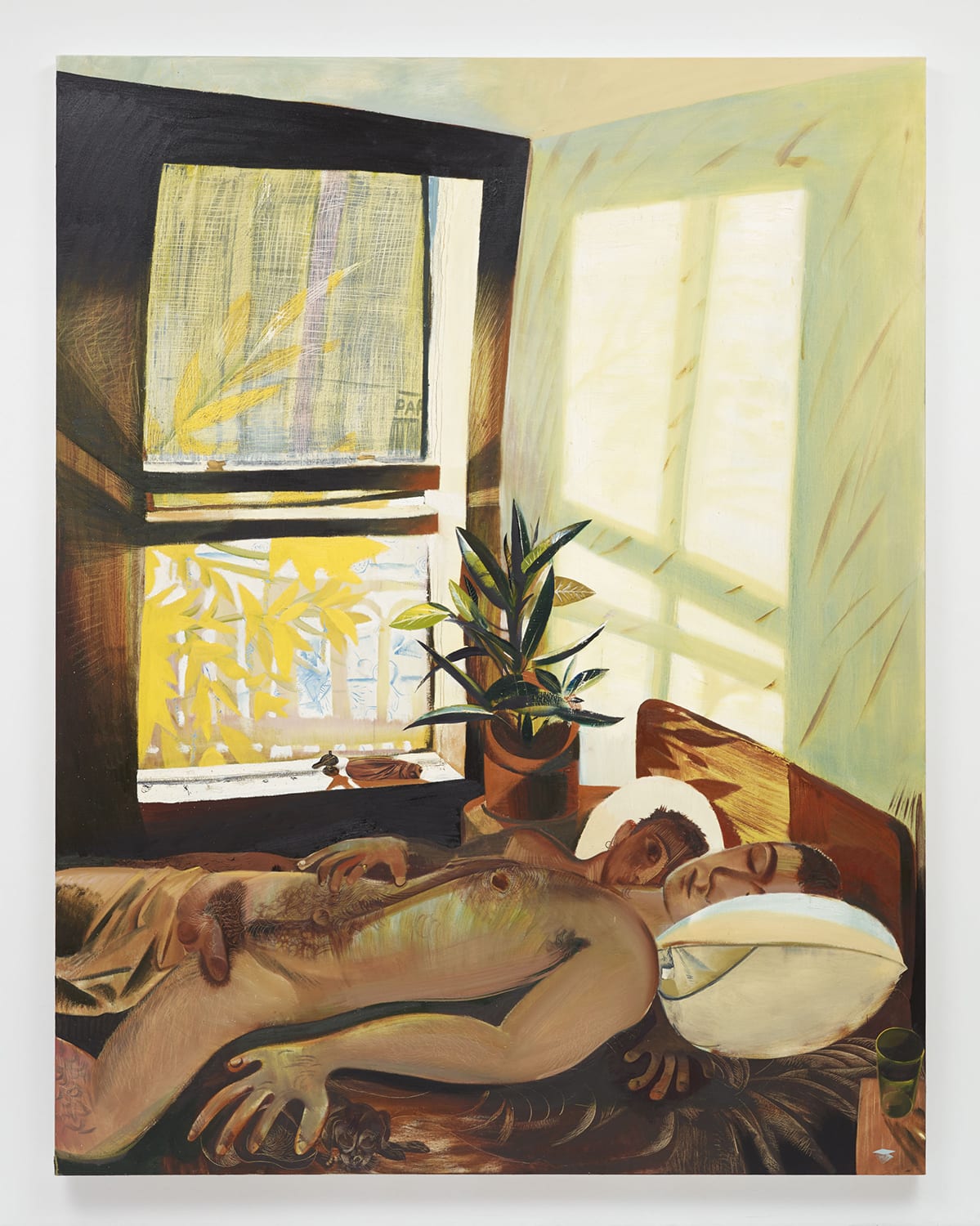

Louis Fratino, Waking up first, hard morning light, 2020. Photo by Jason Wyche. © Louis Fratino. Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York City.

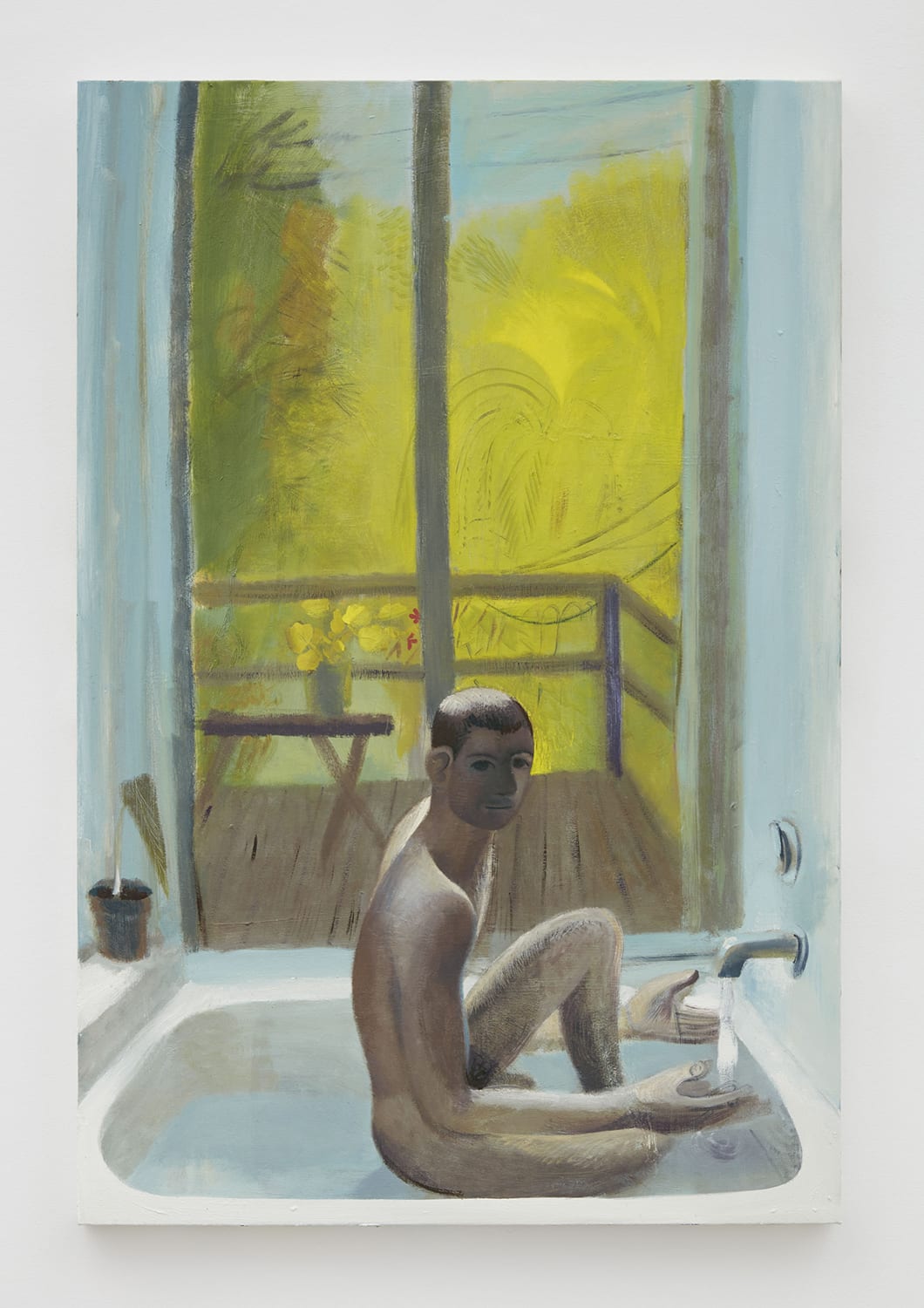

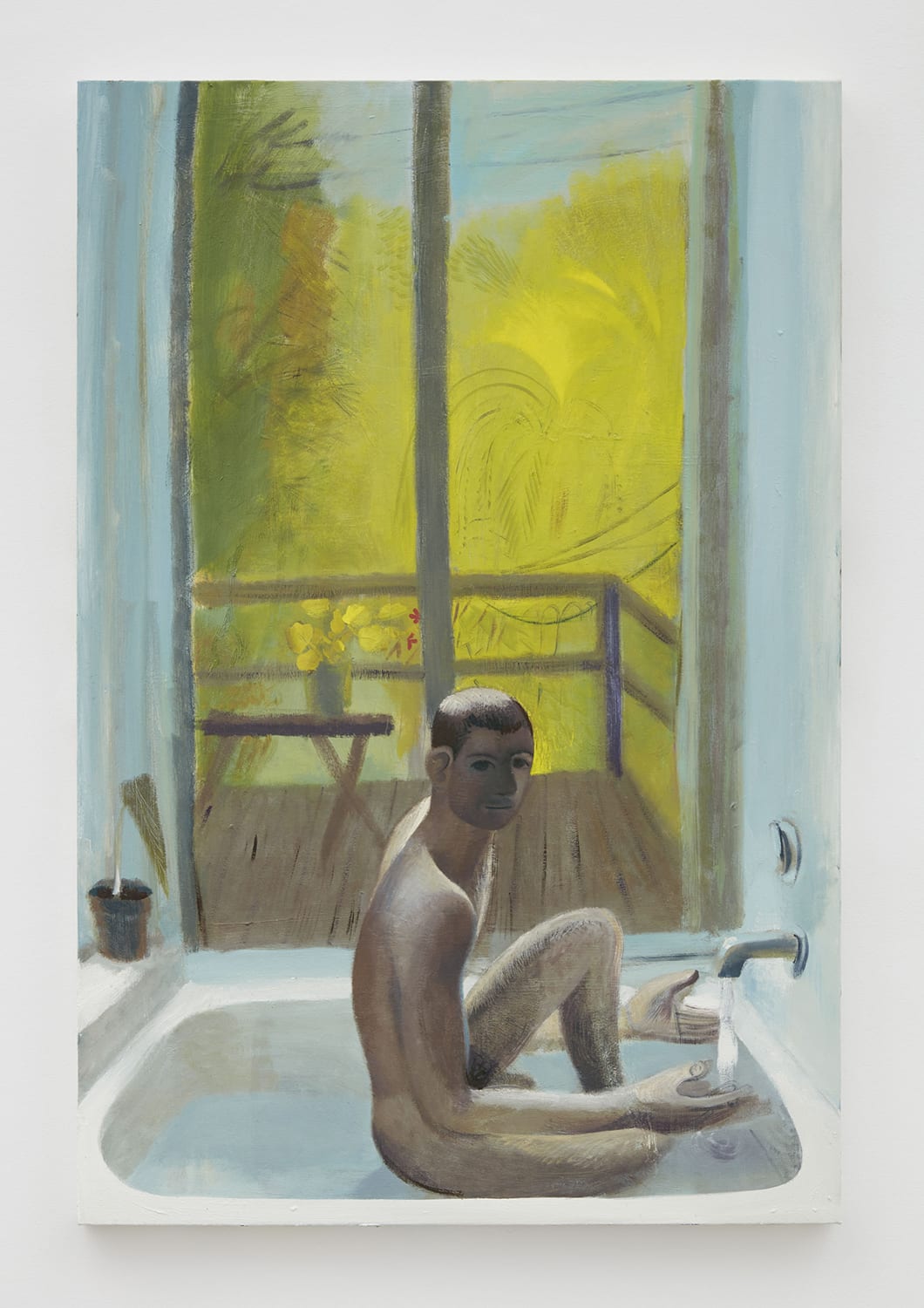

Louis Fratino, Waking up first, hard morning light, 2020. Photo by Jason Wyche. © Louis Fratino. Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York City.  Louis Fratino, July, 2020. Photo by Jason Wyche. © Louis Fratino. Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York City.

Louis Fratino, July, 2020. Photo by Jason Wyche. © Louis Fratino. Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York City.