Left: Portrait of Julien Creuzet © Virginie Ribaut. Courtesy of the artist and High Art. Right: Julien Creuzet, Les Possédées de Pigalle ou la Tragédie du Roi Christophe, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and High Art.

Left: Portrait of Julien Creuzet © Virginie Ribaut. Courtesy of the artist and High Art. Right: Julien Creuzet, Les Possédées de Pigalle ou la Tragédie du Roi Christophe, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and High Art.  Minia Biabiany, Musa Nuit, La Verrière, 2020. © Isabelle Arthuis. Courtesy of the artist.

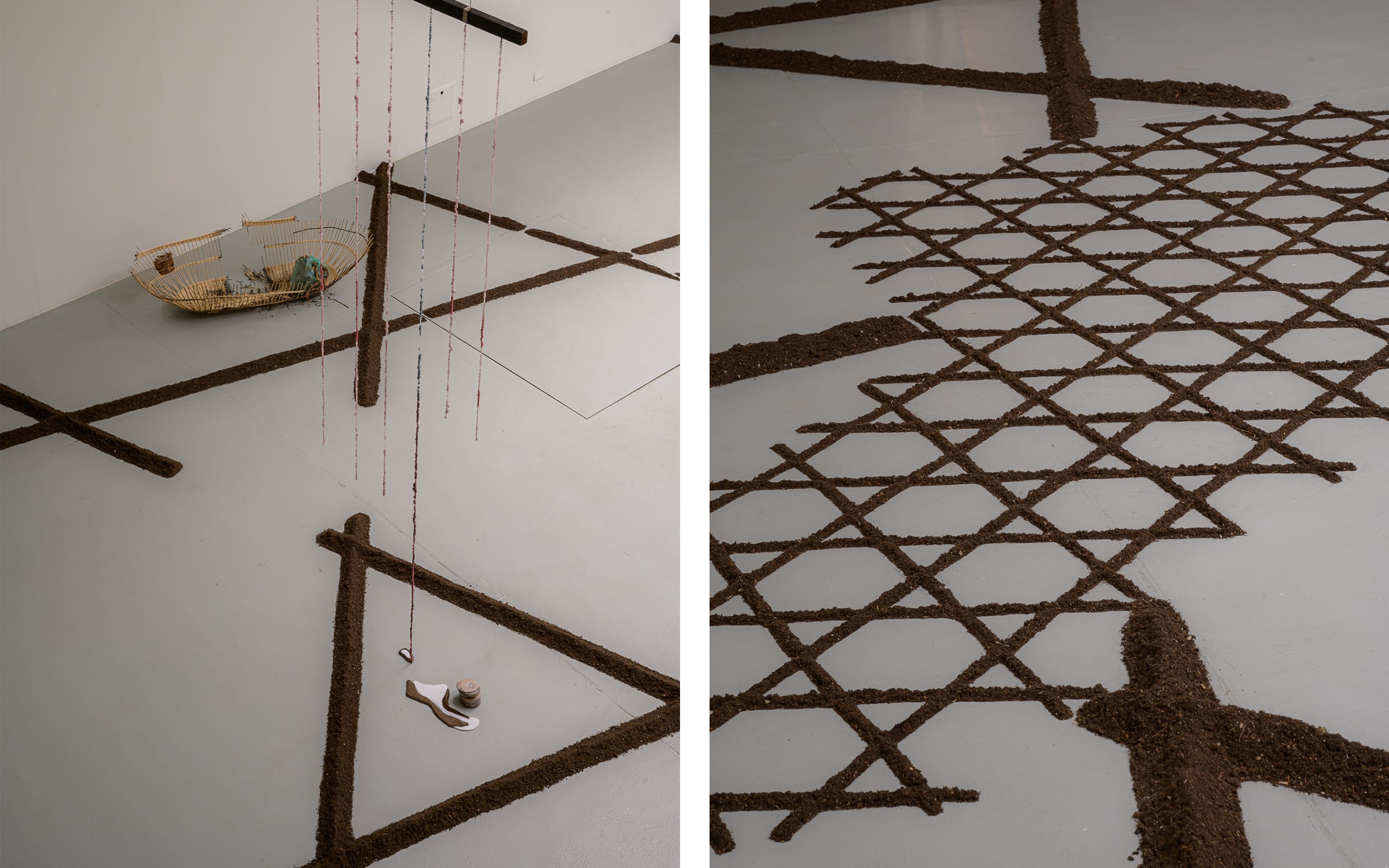

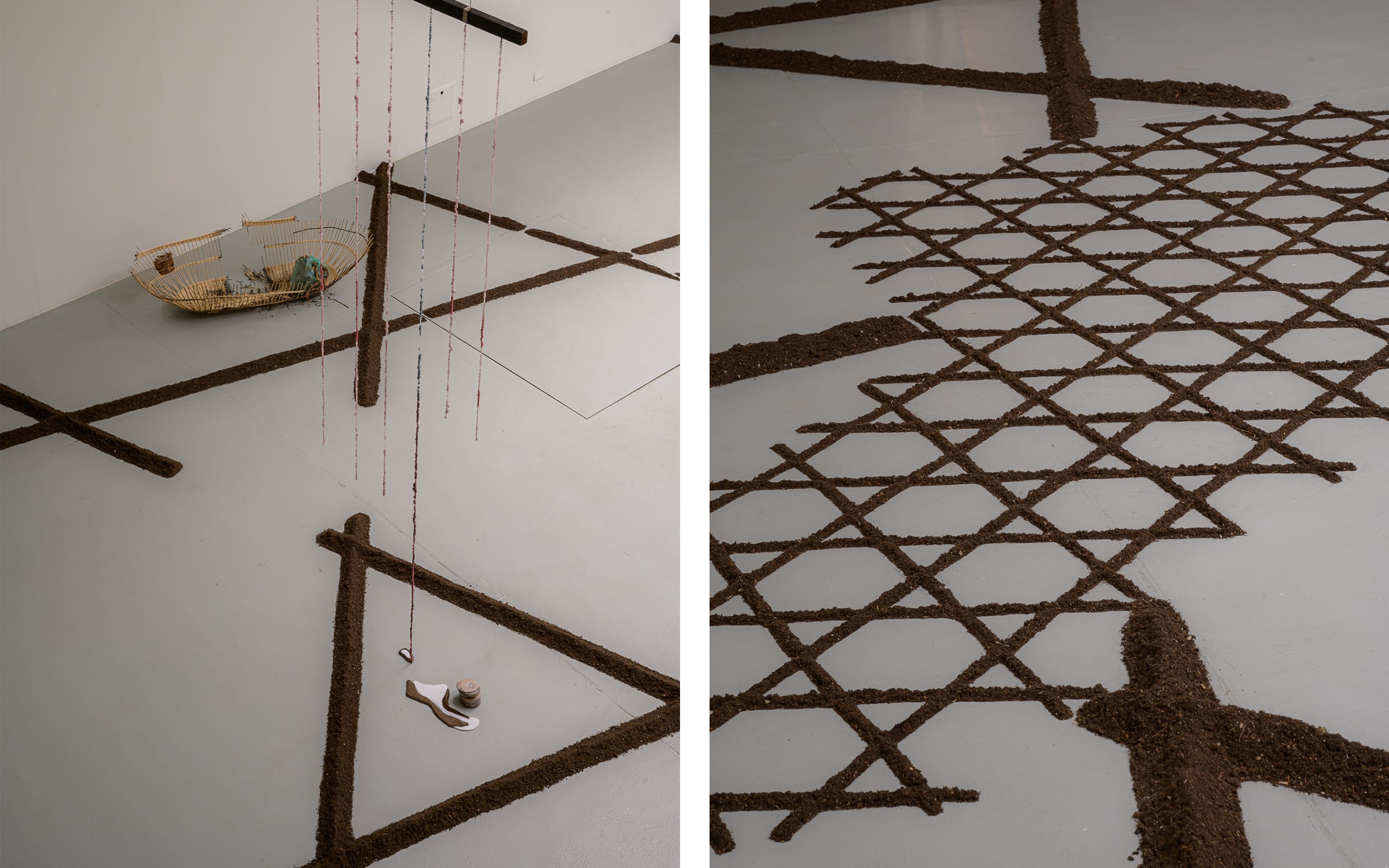

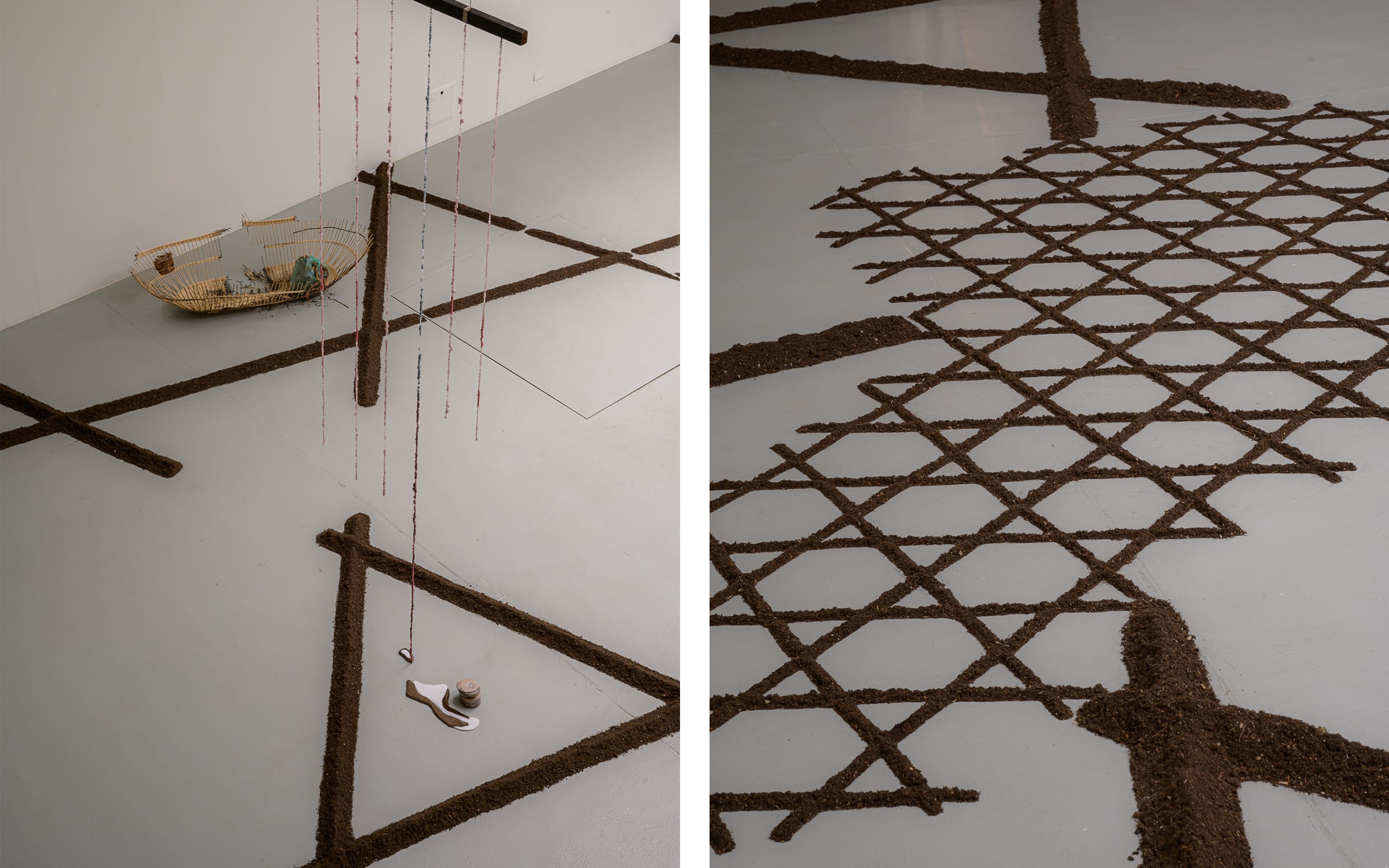

Minia Biabiany, Musa Nuit, La Verrière, 2020. © Isabelle Arthuis. Courtesy of the artist.  Left: Gaëlle Choisne, Map of heart-eagle, 2021-2023. © Aurélien Mole. Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris. Right: Portrait of Gaëlle Choisne, 2023. Photography by Marion Berrin for Paris+ par Art Basel.

Left: Gaëlle Choisne, Map of heart-eagle, 2021-2023. © Aurélien Mole. Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris. Right: Portrait of Gaëlle Choisne, 2023. Photography by Marion Berrin for Paris+ par Art Basel.  Exhibition view of Christelle Oyiri-K, “Gentle Battle” at Tramway, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

Exhibition view of Christelle Oyiri-K, “Gentle Battle” at Tramway, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.  Exhibition view of Christelle Oyiri-K, “Gentle Battle” at Tramway, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

Exhibition view of Christelle Oyiri-K, “Gentle Battle” at Tramway, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.  Minia Bibiany, J’ai tué le papillon dans mon oreille (I have killed the butterfly in my ear), 2021. © Marc Doradzillo. Courtesy of the artist.

Minia Bibiany, J’ai tué le papillon dans mon oreille (I have killed the butterfly in my ear), 2021. © Marc Doradzillo. Courtesy of the artist.  Minia Bibiany, Qui vivra verra, qui mourra saura (Who will live will see, who will die will know), 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Minia Bibiany, Qui vivra verra, qui mourra saura (Who will live will see, who will die will know), 2019. Courtesy of the artist.