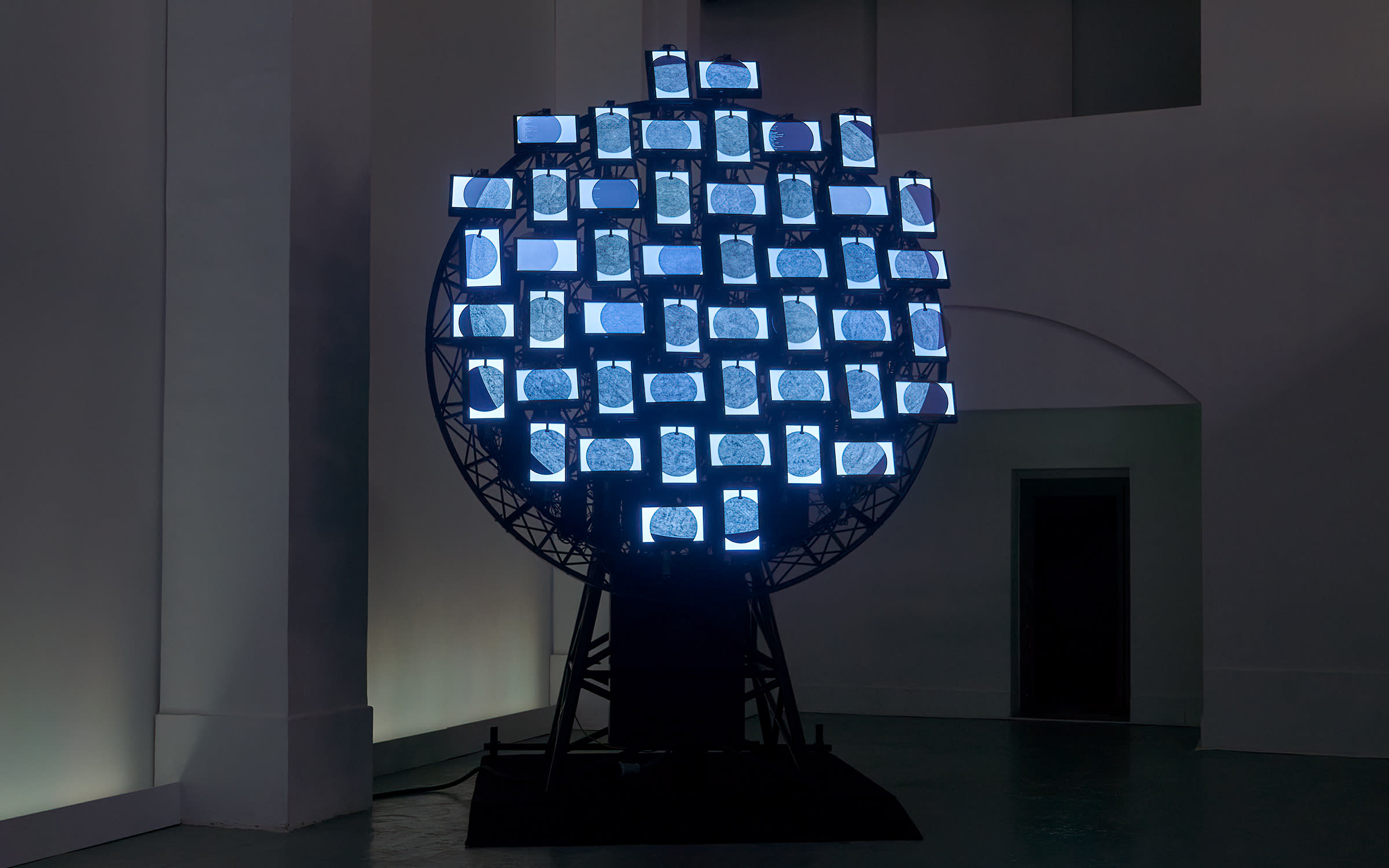

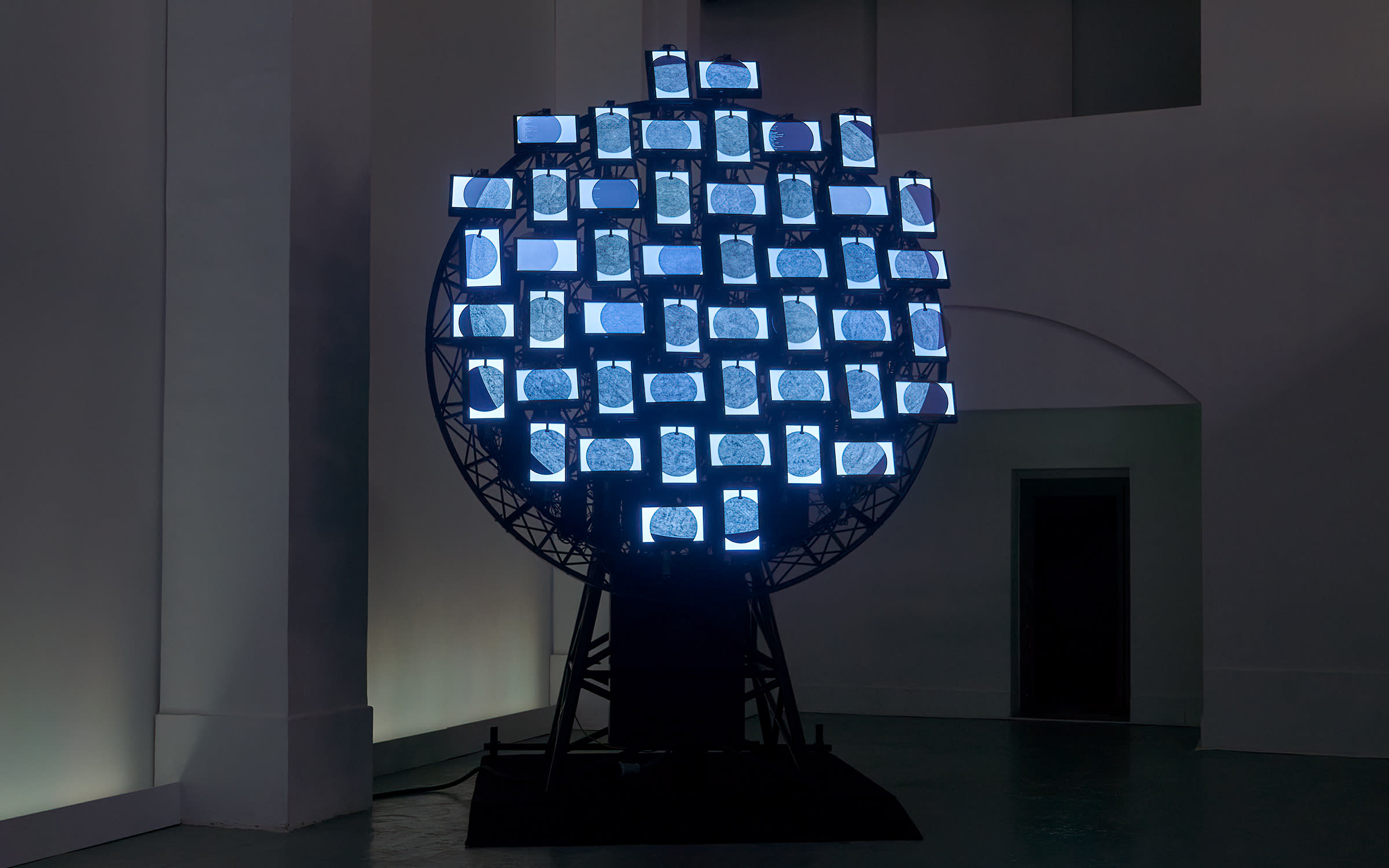

Dancing in the moonlight with Phoebe Hui

The Hong Kong based artist mediates the moon via high-tech robots

Connectez-vous et inscrivez-vous pour recevoir la newsletter Art Basel Stories

The Hong Kong based artist mediates the moon via high-tech robots

Connectez-vous et inscrivez-vous pour recevoir la newsletter Art Basel Stories