Outdoor sculpture parks are perennially popular, but the past year has seen many new additions pop up internationally – this despite rising production and transportation costs. From the Ruinart art garden in Reims, France, and the Solo Sculpture Trail in Matarraña, Spain, to the Goodwood Art Foundation in Chichester, UK, and the Nader Sculpture Park in Miami, US, the number of outdoor spaces dedicated to large-scale sculptural works is on the rise.

A new addition to the international sculpture park scene is coming to Aspen, Colorado courtesy of the Argentine-American businessman and major art collector Jorge Pérez, who hopes to launch his new venture in 2026. He recently purchased the 200-acre property, La Estancia, and has been busy filling the space with monumental works. ‘I love going to the great sculpture parks around the world and I’ve always thought, wouldn’t it be great to have the land to do this?’ Pérez says. So far, he has acquired around 60 sculptures – including pieces by Yinka Shonibare, Robert Indiana, Sam Francis, Fernando Botero, Deborah Butterfield, Sanford Biggers, and Enrique Martinez Celaya – to place around the mountainous site’s many trails.

‘There’s definitely a renewed interest in outdoor sculpture,’ says Ana Paula De Haro, a partner and director at OMR gallery in Mexico City. She notes how there are several intersecting reasons for this: ‘After the pandemic, there was a global shift toward public space and open-air cultural experiences – people are now looking for art that doesn’t require walls or ticketing to access. Institutions and private foundations are also increasingly aware of the social and environmental impact of their programming, and sculpture parks allow for more inclusive, sustainable, and long-term engagement with audiences. Finally, there’s a growing appetite from collectors and cities to make bold, physical statements in the landscape – sculpture offers a way to shape identity and create lasting cultural landmarks.’ At Art Basel’s Unlimited sector this year, OMR brought Atelier Van Lieshout’s The Voyage – A March to Utopia, the largest installation in the fair’s history.

Creating large-scale works has long appealed to artists. ‘Working at scale allows artists to shift the relationship between the viewer and the artwork – it becomes immersive, environmental, even confrontational,’ De Haro says. ‘There’s also a real sense of permanence in outdoor sculpture; it has the potential to live in a landscape for decades, which contrasts with the more transient nature of many contemporary art experiences. For many artists, that’s a deeply compelling proposition, especially when the work engages with public space or natural elements – it opens up new formal and conceptual possibilities.’

However, it is not easy for artists to create large-scale sculpture. ‘It is, and always has been, a privilege – and in the current economic climate, it’s an even bigger one,’ says Sophie Nowakowska, an independent artist manager, curator, and art critic based in London. ‘Rising living costs mean that fewer artists can afford large studios or storage spaces, and the materials needed for durable outdoor work – such as metals, treated wood, stone, and weather-resistant composites – are increasingly expensive,’ she adds.

Amrita Jhaveri, the director of the Mumbai-based gallery Jhaveri Contemporary, says that production costs have risen disproportionately to the price that collectors will pay for big sculptures. Displaying large-scale works internationally, including at art fairs, can also be a challenge. OMR is also ‘more selective now’ when it comes to taking large-scale works to fairs because of shipping costs, De Haro says, but still does so ‘when it makes sense – either because of the fair’s physical capacity, the strategic importance of the presentation, or specific interest from collectors or institutions.’

Shipping costs are usually directly related to the size of the sculpture, rather than its market value (though the two are often correlated). ‘By default, larger pieces and sculptures in particular will be more expensive to move and, like everyone, we have been greatly affected by the cost-of-living crisis,’ says Joe Piotrowski, the director of art handling company Gander & White’s Miami branch. Shipping costs have been increasing more rapidly in the past few years, in particular due to the impact on global energy prices resulting from the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Piotrowski adds. Using sea freight can bring down costs for shipping large works, but is often not quick enough for getting pieces to art fairs and other time-limited exhibitions.

There is a certain challenge, then, to collecting large-scale sculpture that can appeal to some collectors. ‘It’s hard to find good, large sculptures,’ Pérez says. ‘It’s not something that happens every day, like with paintings. You may only find one or two in an auction and galleries don’t often have room for it.’ Pérez says that he typically pays anywhere between USD 100,000 and USD 5 million for a single sculpture, and he finds works in a variety of places. Concerns that tariffs placed by the US President Donald Trump on raw materials such as aluminum and steel would affect the cost of sculpture production have not yet materialized. ‘So far, the tariffs haven’t affected art purchases in Europe or Latin America,’ Pérez says. ‘We have seen an increase in shipping costs and, of course, increases because of the weakness of the dollar versus the euro and the pound.’

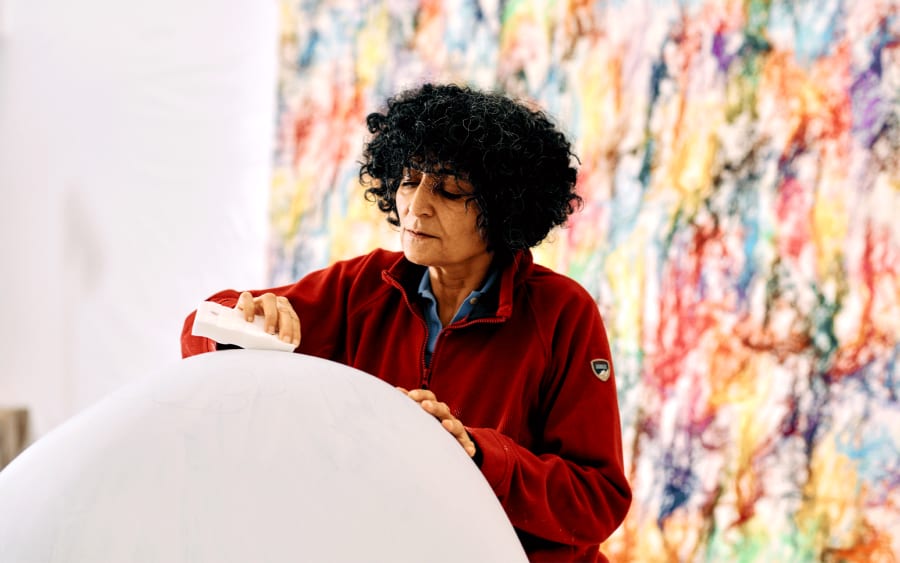

Pérez recently purchased, through Goodman Gallery, a work from William Kentridge’s new series ‘Paper Procession’, which is currently on show at Yorkshire Sculpture Park (until April 19, 2026). Goodman Gallery’s Jo Stella-Sawicka – who was formerly the artistic director of Frieze Art Fair and launched Frieze Sculpture – says that it is easier to purchase monumental sculpture today than ever before, and the offering is more diverse. ‘Previously, it was such a rarefied field that there would be specific artists and dealers you could go to, and they would all be exclusively white men,’ she says. ‘Now, as a collector or a commissioner, you can build significant collections of outdoor sculpture by a much more representative group of artists.’ Stella-Sawicka attributes this to the advent of new technologies, such as 3D modeling; artists increasingly producing works in different parts of the world (such as the gallery’s artist Ghada Amer, who produces her bronzes in China and ceramic works in Mexico); and more galleries taking the risk to invest in artists’ large-scale productions.

The broadening of artists who create large-scale sculpture has also been helped by the selection of more diverse artists for public art commissions, such as Foster + Partners’ winning proposal to design a memorial to Queen Elizabeth II in London, which includes a sculpture by the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare. ‘People are thinking differently about how to make things now,’ Stella-Sawicka says. ‘There’s no getting around it being expensive, but it’s such an exciting field.’

Aimee Dawson is a British writer, editor, and speaker on the art world. Her areas of specialty include art in the digital sphere; art and social media; and Modern and contemporary art in the Middle East.

Caption for header image: Ghada Amer’s Paravent Girls (2021–2023), presented by Tina Kim Gallery, Marianne Boesky Gallery and Goodman Gallery, at the Domaine national du Palais-Royal, as part of the Public Program of Art Basel Paris 2024.

Published on August 28, 2025.