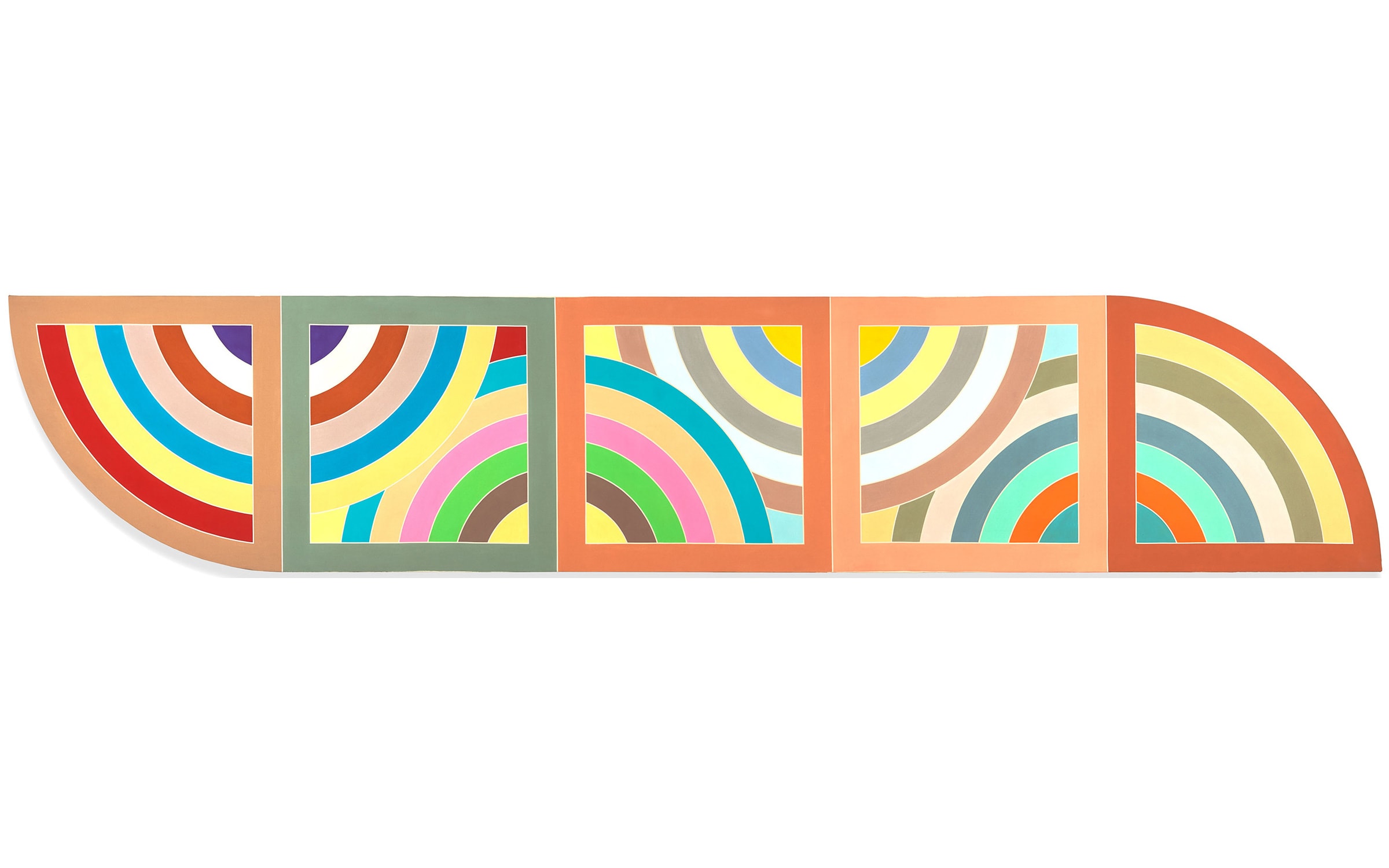

From a rare Frank Stella to a new Sarah Lucas sculpture: discover ten significant works in ‘OVR: Miami Beach’

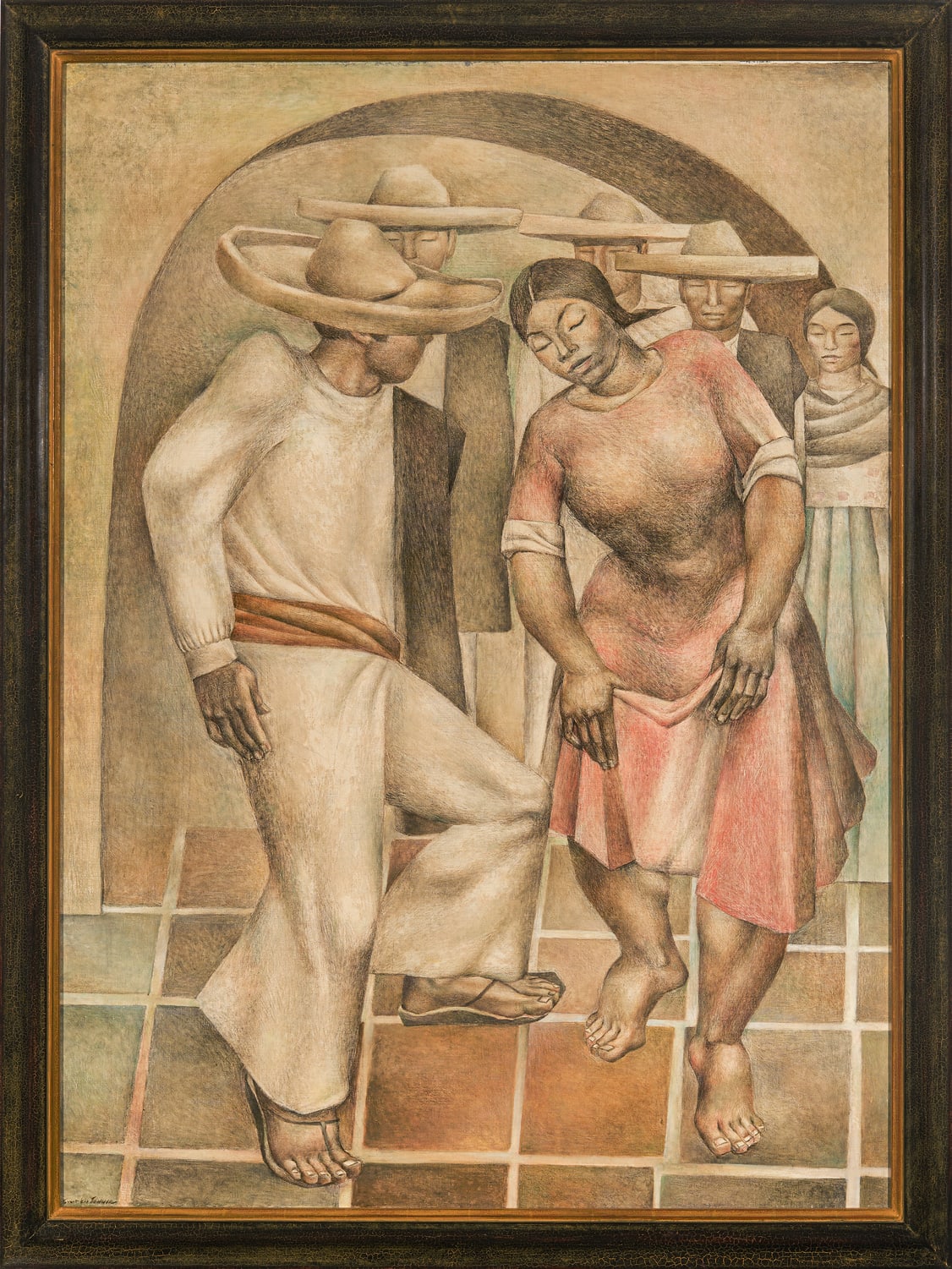

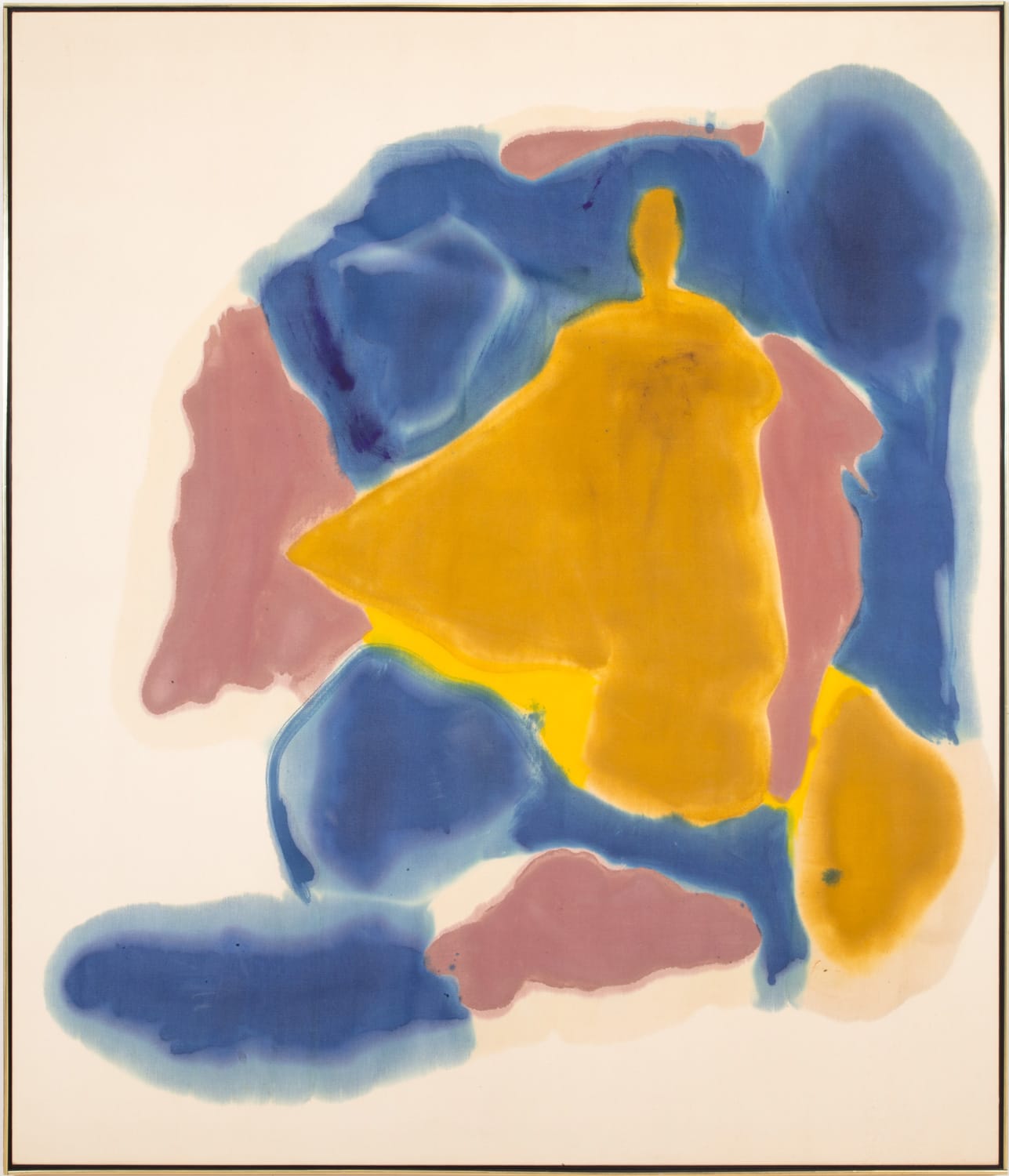

The women of Abstract Expressionism rub shoulders with folk art and contemporary figuration

Log in and subscribe to receive Art Basel Stories directly in your inbox.