There are a few roads in Georgia with the same strange name. One is on Jekyll Island, off the state’s southeastern coast. The road is lined with several flat, wide, expensive homes, and it’s rich with foliage; old trees tower above the houses and some of the branches bend low to the street in dramatic arcs. Another of these roads is in northwest Atlanta, just five minutes by car from Westminster, a private, Christian, and primarily white high school where the 30-year-old artist Tyler Mitchell was once a student. Like its namesake on Jekyll Island, the street is lush and pretty and stately. A classmate of his lived on that street, and she’d throw house parties. Growing up in the South, Mitchell tells me, ʻThere are these almost surreal reminders of your exclusion from certain things.ʼ Back in high school, he was invited to one of the parties. Then he noticed the address: Old Plantation Road. ʻYou can deduce from there how differently I started feeling about the place – from hanging out to realizing, “Oh, yeah, the history is embedded right here. It’s not very distant from me.”ʼ

An idyllic scene with something eerie or rotten just haunting its periphery – the photographer has kept that image, and the history that wrought it, close to him ever since. Recently and most explicitly, Mitchell explored that dichotomy in his spring 2025 Gagosian New York exhibition ʻGhost Imagesʼ. For that body of work, he made portraits on Jekyll Island, where one of the last documented slave ships arrived in 1858, 50 years after the United States officially banned the importation of slaves. He also photographed the neighboring Cumberland Island, which had once been a plantation. ʻI’m actually not trying to center those histories in the work necessarily,ʼ he says. ʻI’m trying to center quiet moments of transcendence or sovereignty in spite of these landscapes, because so many aspects of Black life have thrived and continued on in the face of them.ʼ Gwendolyn’s Apparition, a multiple exposure, shows a Black woman blurring into a dirt path. She is as faded as a memory, but not a memory of suffering; in one of her silhouettes, she’s stretching her arms above her head like a languid dancer. Her body is inextricable from the fraught landscape, but still, she finds her own way to move within it.

ʻGhost Imagesʼ might be Mitchell’s first project to so directly bring American history to the surface, but the artist has long been interested in the tensions or reprieves of a seemingly beautiful image. When we meet at his studio in Gowanus, Brooklyn, he speaks often of quiet, transcendent moments – and of ʻdetonations.ʼ ʻThe intermingling of paradisiacal fun and thorned history is something that detonates my work sometimes,ʼ he tells me, choosing each word with quick, deliberate precision, at the remove of a theorist. There are the quiet detonations of his 2020 monograph, I Can Make You Feel Good, which features highly saturated photos of Black boys and girls at play and at rest, the toys around them – a water gun lifted up, a hula hoop encircling the torso, the long chains of a swing set held in both hands – looking, from one angle, like innocent props and, from another, like bad omens. Mitchell isn’t interested in depicting violence, but he also won’t indulge easy escapism.

He started developing this language while still an undergraduate at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, while studying film, finding a mentor in the renowned photographer and historian Deborah Willis and making a name for himself directing music videos for indie artists like Abra and Kevin Abstract. The video for the latter’s 2014 track ʻHell/Heroinaʼ is an early rendition of the style Mitchell would come to be known for: in the final moments, Abstract rides a carousel, but the childlike setting has a tragic touch, due to the washed-out colors and the camera’s slightly disorienting camera angle, the rapper’s blank gaze bobbing in and out of view. Mitchell was catapulted to household-name status in 2018 when he photographed Beyoncé for Vogue’s September issue and, in so doing, became the first African American and one of the youngest to shoot their cover. In the meantime, he’d been steadily picking up fashion campaigns with brands like Marc Jacobs, Givenchy, and Converse and, later, Loewe, Dior, Gucci, and Prada, to name a few. This year, he shot the catalog for ʻSuperfine: Tailoring Black Styleʼ, the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute that informed this past spring’s Met Gala; instead of merely documenting the show, Mitchell created an additional 30-page photo essay of models in both vintage and contemporary garb. He also walked the red carpet, a dandy in cream, white feathers, and a touch of royal blue, all courtesy of the designer Grace Wales Bonner, a collaborator and inspiration of his.

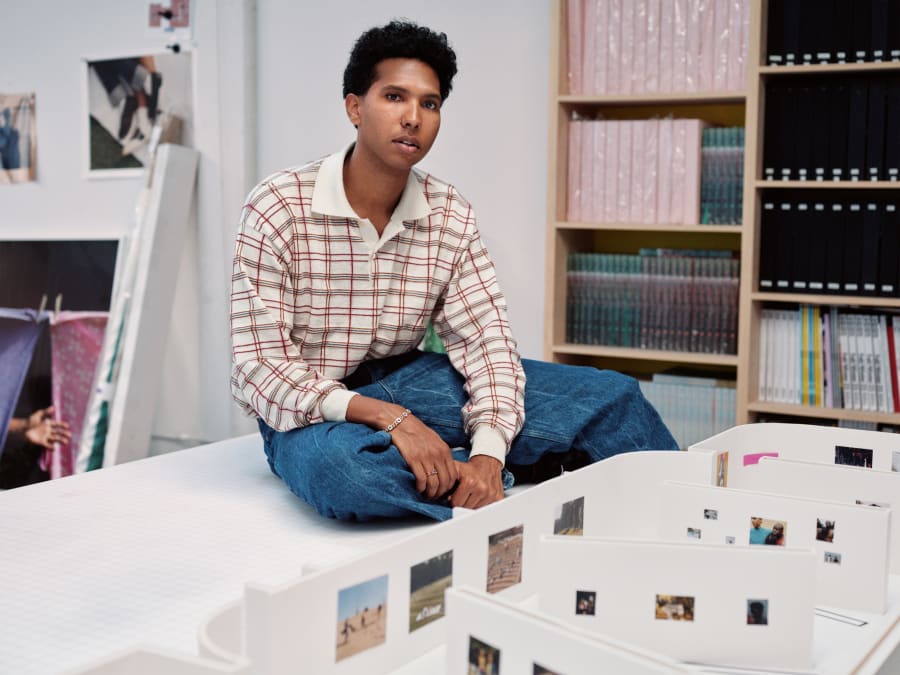

Mitchell’s studio is neat and as carefully styled as the artist himself. (The only time he loses his train of thought in our conversation is when he remarks, mid-sentence, that his loafer is busted, zeroing in on a flaw that my eyes, at least, cannot perceive.) We’re each lounging on cushy, mocha-brown leather sofas, though when the talk turns to his library, Mitchell gets excited, moving in a whirl to show me the various photo and art books he’s been thumbing through recently. At the moment, he’s looking into the work of Hughie Lee-Smith, an African American painter whose scenes of isolated Black and white figures in outdoor landscapes he felt an immediate connection to. ‘They’re quietly beautiful, sometimes bucolic,ʼ he says. ʻThere’s a real sense of play.ʼ He studies each page closely, savoring it, as he flips through the book now. (When he reaches the artist’s biography in the back, we realize that Lee-Smith spent his formative years in Atlanta, too.) Thelma Golden, chief curator and director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, recently told Mitchell about Lee-Smith’s frequent inclusion of figures holding bunches of balloons, a signature in the photographer’s own work, as seen in his 2022 portrait Treading. In that image, a Black boy is submerged in a lake, only his head above the surface, his eyes closed either serenely or resignedly, and beside him, also peeking above the water, is a bouquet of rainbow-colored balloons – Mitchell’s way of giving the boy and the viewer that sense of play, that precious buoyancy.

At Mitchell’s desk, there’s also a book on the Gee’s Bend quilters, a group of cross-generational women from Alabama whose work is featured in Mitchell’s early-career survey show ʻWish This Was Realʼ, which opened at C/O Berlin in 2024 and will travel to the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris this October, after a stop at Lausanne’s Photo Elysée Museum this summer. In Berlin and Lausanne, Mitchell used the show as an opportunity to gather several of the artists who have been his north stars and those with whom he finds himself in dialogue; in addition to the quilters, there’s work by Wales Bonner, the filmmaker Garrett Bradley, and the conceptual artist Rashid Johnson, among others. ʻIncreasingly, I’m drawing to mediums outside of photography,ʼ he says. ʻIʼm excited by sculptors and quilt makers, textile artists, and some painters here and there.ʼ This eye toward other mediums is apparent in ʻGhost Imagesʼ: several of the photos are printed on unexpected materials like mirrored glass and thin, draped cloth. Mitchell also has several monographs by Wolfgang Tillmans, who he considers one of the most important photo artists alive. He’s inspired by the German photographer’s ability to shift nimbly between fashion and fine-art images, and to erase the boundaries between them along the way. ʻFor decades on end, the photography world has been grappling with this unanswerable question of how to privilege a documentary practice versus a conceptual practice versus a staged photographer’s practice,ʼ Mitchell says, picking up speed as he goes. ʻI think it’s interesting that we’re still, to a degree, in the muck of debating those things, when Contemporary art and Postmodernism have jettisoned all of that long ago.ʼ He laughs a bit, to himself, and leans back, thinking it through.

In his own practice, Mitchell is dogged about not differentiating between commercial and personal work, as exemplified in his latest monograph, which takes its title from his survey exhibition, ʻWish This Was Realʼ – a phrase which itself speaks to his interest in muddling the line between the artificial and the biographical. He calls it the ʻintervention of his own yearningʼ – admitting to an image he wants but does not have, not really. Mitchell doesn’t privilege any documentary ʻtruthʼ in his photos. Oftentimes, he says, he wants to let the viewer know there’s an intervention. In certain instances, he’s placed himself, camera in hand, within the frame. It seems, on the one hand, to be an intellectual experiment: a way to fully shatter the boundaries between the photo as an objective witness, an art object, and a staged scene. It seems, on the other hand, to be the most vulnerable kind of play – an honest game of pretend. It’s Mitchell showing his hand. He knows the beauty is not all real. He knows there’s a shadow at the edge. He asks us to look anyway.

Nicole Acheampong is a writer based in New York. She is an editor at T: The New York Times Style Magazine.

Tyler Mitchell, ʻWish This Was Realʼ at La Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris (October 15, 2025 – January 25, 2026)

Tyler Mitchell is represented by Gagosian (New York, Basel, London, Hong Kong, Paris, Rome).

Caption for header image: Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Red Steps), 2016 © Tyler Mitchell. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

Published on October 6, 2025.