藝術家烏曼(Uman)的作品是關於對比之美的一場深度探尋。畫面中,那些看似不和諧的色彩組合,卻以萬千姿態變幻,與她於畫布上精心營造的動態圖案及肌理效果交相輝映。烏曼的畫作引人駐足,凝神細觀,在迷離之間彷彿能窺見靈動身影;而另一些,如《Zam Zam Bom Bom》(2023),則將觀者瞬間捲入一場喧囂盛宴,視覺衝擊力十足。她標誌性的球體元素,散發著璀璨光芒,以一種輕盈的舞姿在畫面中游弋,周圍纏繞著鋸齒狀線條與起伏的餘弦波。在畫布的其他區域,如同書法般的迴旋筆觸,掙脫了構圖的束縛,盤旋於畫面邊緣,似乎渴望突破畫框的限制。

這些繪畫技法在她近期作品中反覆出現,也預示著藝術家一次重大的遷徙。在紐約居住二十載後,她計劃於明年春季移居法國南部。

烏曼對「移居」一詞並不陌生。上世紀80年代,她的家庭在索馬里內戰期間逃離家園,抵達肯亞蒙巴薩(Mombasa),她在那裡度過了青少年時期,之後又移居丹麥。為了追求更自由、更穩定的創作環境,烏曼於21世紀初選擇移民美國,定居紐約。正是在這座城市,她開始了自學繪畫的藝術探索。2010年,她北遷後,終於尋得了可以靜心創作、揮灑創意的僻靜之處,這段時期也成為了她藝術創作的黃金時代。

在那裡,烏曼得以自由探尋自身的藝術語言。其早期作品描繪了她在林間的新環境,她沉醉於此,著筆於樹木、飛鳥與自畫像,目光流連於季節流轉的瞬息之美。當時,她嘗試具象畫與拼貼,選用了大地色調及憂鬱沉靜的配色。2015年,她在紐約White Columns的首次個展,展出了神秘的人物肖像以及抽象、混合媒介作品,色彩從陰影般朦朧幽暗的背景後隱現,呼之欲出,意圖佔據視覺中心。隨著創作上的不斷探索,她對紡織品與時裝的熱情也逐漸融入作品之中,那些明艷活潑的色彩,令人想起她在肯亞童年宅邸中無處不在的繁複織物美學。「我們很喜歡圖案,」烏曼近期在工作室的一次視像通話中分享道,「這是我成長的文化。從地板到天花板,處處皆是圖案。我的母親喜歡重新裝飾傢俱,祖母擅長鉤編,家中總能看到鮮豔多彩的新物件。」

首次個展迅速讓這位藝術家在藝術界聲名鵲起,隨後個展與群展邀約不斷。烏曼目前居住在紐約州中部的Cooperstown,並計劃在她前往法國期間,繼續維持位於奧爾巴尼(Albany,約90分鐘車程)的工作室運作。她坦言此次搬遷心情複雜,她的首次機構個展「Uman: After all the things...」上個月在奧爾德里奇當代藝術博物館(Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum)開幕。這場展覽由Amy Smith-Stewart策劃,似乎標誌著她一個創作時代的落幕。「在紐約生活了二十年,這就好像是在告別這段歲月,」她說道,「在奧爾德里奇的這場展覽,是我寫給紐約上州生活的情書。」

在奧爾德里奇的Project Space裡,她標誌性的球體構成了巨幅壁畫,懸浮於展廳四壁。《Melancholia in a Fall Breeze》(2025)由籃球大小的黑色圓形色塊組成,沿著拱形白牆,從高處窗戶傾瀉而下。在空間中央,烏曼安裝了一件牧羊人手杖造型的大型街燈雕塑,由加州工匠以廢金屬和吹製玻璃打造。這盞燈的形象也出現在雕塑後方牆壁上懸掛的一幅畫作中,燈身散發出絢爛多彩的光暈,宛如飄落的樹葉。兩件作品的靈感皆來源於她奧爾巴尼工作室附近的一盞街燈。「搬到紐約上州後,我的創作開始轉型,煥發了新的面貌,」她說道,「這盞燈已成為光明、探索與創意覺醒的象徵。散佈在壁畫牆上的圓點和雪花形態,延續了同樣的精神,它們自然的韻律、動感與流動,都是我生命中的微小印記。」在這盞街燈雕塑落成的歡慶時刻,烏曼解下頸間絲巾,將其系於燈柱基部。自此,絲巾也成為展覽的一部分。「直覺告訴我,我必須在這個空間裡留下自己的一部分,」她解釋道,「這樣一來,燈就成了我的自畫像。」

在奧爾德里奇的展覽(10月19日開幕)之後,同月月底,她在紐約Nicola Vassell藝廊的個展「I Love You After Everything」也相繼拉開帷幕。這兩場展覽,既是對其過往的深度內省,亦是對迫使她遷居的當下境遇的回應。「我認為,這兩場展覽,都是我發自內心的喜悅之產物,」她說道,「但我也想說,喜悅是相對的。 今年並非坦途,我歷經了不少艱難時刻,這些體驗都已融入我的作品之中,你們或許能從中窺見心碎、痛苦,以及失落的痕跡。」

步入2025年,一股令人熟悉的暴力與壓制浪潮在美國社會再度湧現,讓藝術家們感到在此地生活既不安寧也不安全。「美國正在改變,」她說道,「這讓我重新覺得自己像個需要逃離的移民。我當初來這裡是為了尋求平和與寧靜,但現在,尤其是在今年,這兩種感覺都消失了。」眼前的景象無疑觸動了烏曼一些童年記憶,她一直試圖在作品中以明亮、充滿活力的色彩主題來平衡和消解這些陰影,同時,她也巧妙地將怒火傾瀉在畫布上。「在Nicola Vassell藝廊的一幅畫中,藏著一個豎中指的圖案,」她笑著透露,「有人說它看起來像被子,但走近看就會發現一根中指。我在畫中添加的這些細節,是我在作品中開的小玩笑。」

烏曼正在嘗試以個人攝影作品為元素創作新的拼貼畫,同時為2026年在巴德學院赫塞爾藝術博物館(Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College)舉辦的回顧展準備一個全新的幾何繪畫系列,該展覽由藝術總監Lauren Cornell策展。 這些馬賽克般的構圖,令人想起她年少時常去的肯亞沿海小鎮那些瓷磚拼貼的牆面與壁畫。展望前路,烏曼也開始探索新媒介,並期待著遷居至法國Bagnols-sur-Cèze後的新生活。「我會重複當年遷居紐約上州時的做法,先安頓下來,重新熟悉環境,找到自己的生活節奏。然後打造一個工作室,讓它成為我的專屬天地,」她說道,「我嚮往這樣一個地方,在那裡我可以放鬆下來,悠閒漫步,河中暢遊,享受寧靜的生活。」

Colony Little是一位常駐北卡羅來納州羅利的作家和藝評家。她是Culture Shock Art的創辦人,這是一個致力於放大黑人藝術家、女性和有色人種藝術家聲音的當代藝術博客。2020年,她榮獲了安迪.華荷基金會(Andy Warhol Foundation)藝術作家資助。

「Uman: After all the things…」於康乃狄克州里奇菲爾德市的奧爾德里奇當代藝術博物館展出,展期至2026年5月10日。

烏曼由豪瑟沃斯畫廊(蘇黎世、巴塞爾、香港、倫敦、洛杉磯、紐約、巴黎、薩默塞特、聖莫里茨)與Nicola Vassell藝廊(紐約)代理。兩間藝廊將在巴塞爾藝術展邁阿密海灘展會的「藝廊薈萃」(Galleries)展區呈獻藝術家的作品。

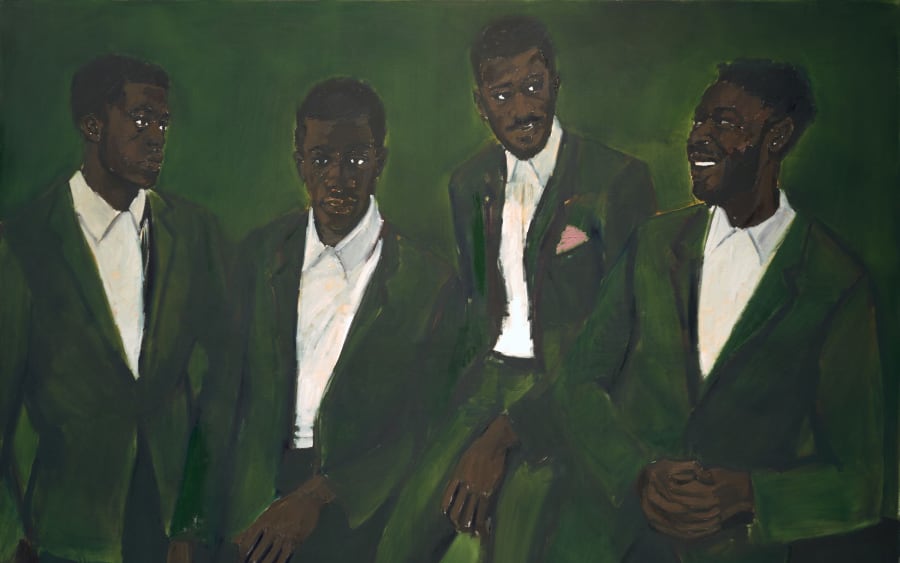

頁頂圖片標題:烏曼,《grid painting #7》,2025,圖片由藝術家、Nicola Vassell藝廊及豪瑟沃斯提供

2025年11月13日發佈