Tashkent’s Centre for Contemporary Arts opens, bridging past and present

In September 2025, the Centre for Contemporary Arts Tashkent opens – a project by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, led by Gayane Umerova – marking a bold step toward a vibrant cultural scene in Central Asia

Tashkent’s Centre for Contemporary Arts opens, bridging past and present

In September 2025, the Centre for Contemporary Arts Tashkent opens – a project by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, led by Gayane Umerova – marking a bold step toward a vibrant cultural scene in Central Asia

Tashkent’s Centre for Contemporary Arts opens, bridging past and present

In September 2025, the Centre for Contemporary Arts Tashkent opens – a project by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, led by Gayane Umerova – marking a bold step toward a vibrant cultural scene in Central Asia

Tashkent’s Centre for Contemporary Arts opens, bridging past and present

In September 2025, the Centre for Contemporary Arts Tashkent opens – a project by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, led by Gayane Umerova – marking a bold step toward a vibrant cultural scene in Central Asia

Tashkent’s Centre for Contemporary Arts opens, bridging past and present

In September 2025, the Centre for Contemporary Arts Tashkent opens – a project by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, led by Gayane Umerova – marking a bold step toward a vibrant cultural scene in Central Asia

By George Nelson

The layers of Uzbek heritage jostle for position on Tashkent’s skyline. Arabs, Persians, and Genghis Khan arrived on the Silk Road, followed by Imperial Russians, the Soviets, present-day Uzbeks, and many more. They have all left their mark on the capital’s 2,000-year history. The tiled turquoise domes of mosques shimmer in the heat next to modernist masterpieces like the 17-story Hotel Uzbekistan and the monumental, Leonid Brezhnev-era Peoples’ Friendship Palace. Then there are the silver skyscrapers of new commercial developments, built to reflect the ambitious, progressive vision of Uzbekistan’s ruling class. Tashkent and its 3 million diverse inhabitants are forever in flux, grappling with their past while reaching for the future within a global cultural landscape.

Several of these urban regeneration projects have replaced historic neighborhoods (mahallas) and post-war, Soviet architectural landmarks, including the concrete House of Cinema. Built in 1982, it was removed in 2017 to make way for the ongoing construction of Tashkent City, the gleaming, white marble centerpiece of Uzbekistan’s new architectural era. Tashkent’s ambition to position itself as a modern cultural and economic hub in Central Asia has led to significant architectural transformation.

Yet not all projects represent a trade-off – among them is the flagship project, the Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA), spearheaded by Gayane Umerova, Chairperson of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF). This marks a significant milestone in her long-term vision of establishing a dynamic, interdisciplinary platform for cultural production and artistic exchange in Uzbekistan. Born and raised in Tashkent, she led the transformation of the historic site, securing the building, commissioning Studio KO for its architectural revival, and appointing Dr. Sara Raza as artistic director – shaping the CCA’s mission from inception to realization.

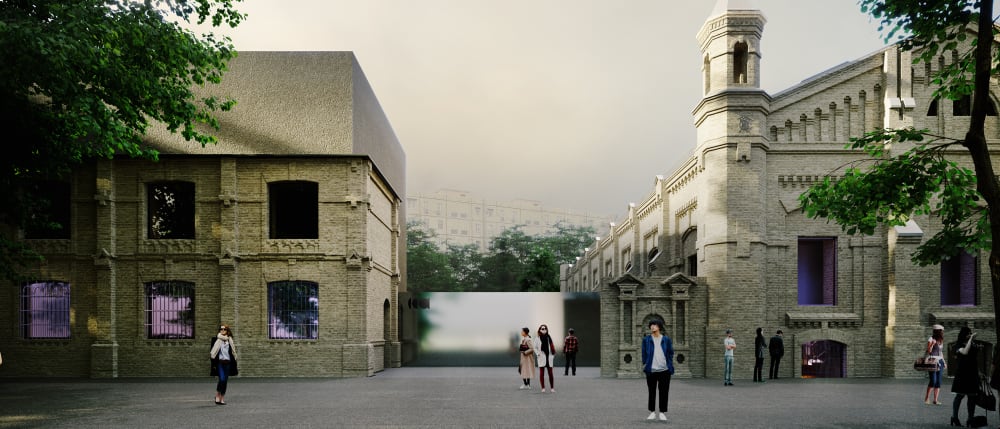

The CCA is housed in a former tram depot and diesel power station built in 1912. It is slated to reopen in September and will preserve the Uzbek capital’s historic identity while developing its creative economy. The ACDF is proving that it’s possible to do both, not only through the CCA, but also by reconstructing the State Museum of Arts, the State Children’s Library, and the residence of the Grand Duke Romanov, among other projects.

In her mission to propagate contemporary Uzbek culture, London-born and New York-based Raza is looking back to Tashkent’s role in early-20th-century thinking, Soviet-era creative movements, and the legacy of Modernist architecture. These deep-rooted histories inform Tashkent’s contemporary identity.

‘Tashkent’s cultural scene has a fascinating 20th-century modern cultural foundation, which hasn’t been fully revealed to the West and has remained largely within the intellectual sphere and behind an iron curtain due to Cold War politics,’ Raza says.

The early 20th century was a period of significant religious, artistic, and intellectual transformation in Tashkent. Take the Jadids, for example – a progressive movement of Muslim intellectuals who emerged at the turn of the 20th century in Turkic-speaking parts of the Russian Empire. Today, many Uzbeks view them as enlightened founding fathers – and modern-day role models – for advocating a European-modelled cultural reformation. Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Uzbekistan’s president, is not shy of extolling the movement’s doctrines in his speeches and in January called for nationwide celebrations to be held this year to mark the 150th anniversary of the birth of Mahmudkhoja Behbudi, a key figure in the Jadid movement.

The rise of Soviet power led to the Jadids’ demise in the 1930s and positioned Tashkent as a beacon of socialist achievements in the East. Modernist monuments started punctuating the skyline, including the Constructivist Government House built in 1931. Tragically, an earthquake razed Tashkent to the ground in 1966, but in chaos the Soviets saw opportunity and jumped on the disaster to refashion the city in the image of a modern socialist metropolis. The Modernist buildings that followed lie at the heart of the city’s current identity crisis, with dozens recently erased to make way for sparkling buildings encased in white marble.

The ACDF, through initiatives like the international exhibition Tashkent Modernism. Index and the Tashkent Modernism XX/XXI research project, is conserving the Uzbek capital’s heritage ‘with preservation ambitions of modernist architectures on a global scale,’ the foundation says. The imminent reopening of the CCA is the next chapter in the foundation’s mission.

‘Tashkent’s identity is layered and multifaceted – our challenge is to create space for contemporary art while recognizing and highlighting the city’s remarkable architectural legacy,’ Gayane Umerova says. ‘Rather than presenting a single narrative, we invite artists and communities to engage with the full richness of the city’s heritage, from the social fabric of the mahalla living quarters to the treasures of Tashkent’s modern architecture, and to the CCA, a rare example of 1912 industrial architecture.’ She adds that she wants the CCA’s vision to be a catalyst for the entire region, ‘supporting talent, nurturing critical discourse, and fostering connections between Uzbekistan and the global art world.’

By adapting the former tram depot for contemporary art, the foundation wants contemporary artists to be inspired by the capital’s history, which Gayane Umerova says, ‘draws on Tashkent’s multifaceted Silk Road heritage, long-standing traditions of craft, and a centuries-old spirit of exchange.’

She remarks: ‘Through our programming at the CCA, we invite artists to explore these connections and encourage discovery of the building’s many historical layers and cultural meanings.’

The CCA’s program will include exhibitions, artist residencies, workshops, and educational initiatives. The CCA Artist Residencies are in the historic mahallas

of Namuna and Khast Imom. Raza explains that Uzbekistan’s diverse population, which includes Russians, Tatars, Koryo Saram, Tajiks, and Uighurs, will be reflected in the institution’s outlook alongside Tashkent’s architectural legacy.

‘As someone of mixed ethnicity, it is essential for me to be inclusive in a horizontal manner,’ she says. ‘Furthermore, much of my artistic direction, as well as the forthcoming curatorial projects and public programs, will reflect this plurality and diversity on the rich heritage of Uzbekistan. I am interested in exploring this via the lens of contemporary artists and thinkers.’

Raza adds that she is particularly interested in ‘reviving Tashkent’s history in the 20th century as a center for the Global Majority world, rethinking the city as a model for globally engaged future exhibitions and public programming that celebrate local and Global South-South connections in new and dynamic ways, capturing the spirit of diversity.’

As well as tasking Studio KO, founded by Olivier Marty and Karl Fournier, with renovating the CCA, the ACDF also commissioned the duo to design the buildings to be used for the CCA Artist Residencies. ‘We share a sensitive approach to heritage, the same desire to build without destroying, to think about conversion and rehabilitation rather than wiping the slate clean, which is often the easiest thing to do,’ Studio KO says. It is easy to see why the practice’s ethos dovetails with the ACDF’s outlook.

Studio KO’s interventions at both the residencies’ locations have been subtly introduced in a bid to seamlessly merge history with forward-thinking creativity. At the Namuna site, the mosque was carefully renovated with local builders, carpenters, and masons and is now an exhibition hall, while a restored ayvan – a traditional terrace – will host events and a new building designed by the studio houses a café and workshops. The Khast Imom mahalla includes a former kindergarten, now Central Asia’s first dedicated curatorial library.

‘Through projects like Tashkent Modernism XX/XXI, which my team and I launched in 2017 to protect and reinterpret the city’s modern architectural sites, and through the revitalization of the Namuna and Khast Imom mahallas for the CCA’s artist residencies, as well as the launch of the CCA, we highlight different chapters of this architectural story,’ Gayane Umerova says. ‘These efforts ensure that our contemporary art initiatives remain deeply rooted in a spirit of respect and ongoing dialogue with the past, allowing each generation to find its own inspiration in the city’s evolving landscape.’

The Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF) preserves and promotes the country’s rich cultural heritage while advancing its creative economy. Its initiatives include the Uzbekistan Pavilion at Expo 2025 Osaka Kansai, the Uzbekistan National Pavilion at the Venice Biennale (Art and Architecture), the Aral Culture Summit in Nukus, the new Uzbekistan National Museum by Tadao Ando, and the Bukhara Biennial. Opening in September 2025, the Centre for Contemporary Arts Tashkent—housed in a restored 1912 building—will serve as a dynamic platform for contemporary art, dialogue, and public engagement, connecting Uzbekistan’s cultural legacy with global creative practices.

Caption for header image: Centre for Contemporary Arts Tashkent. Renders courtesy of Studio KO and Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation.

Published on July 3, 2025.