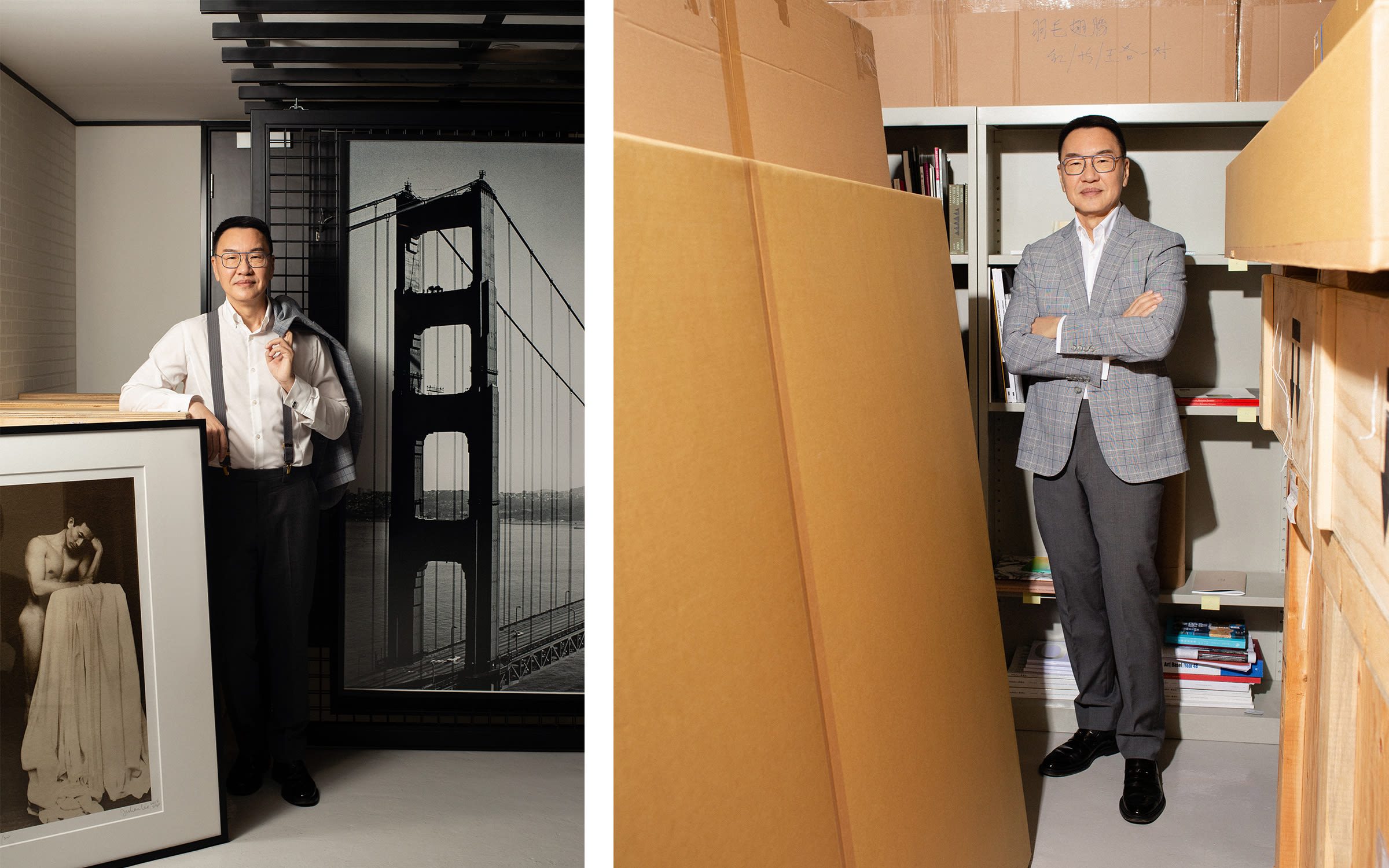

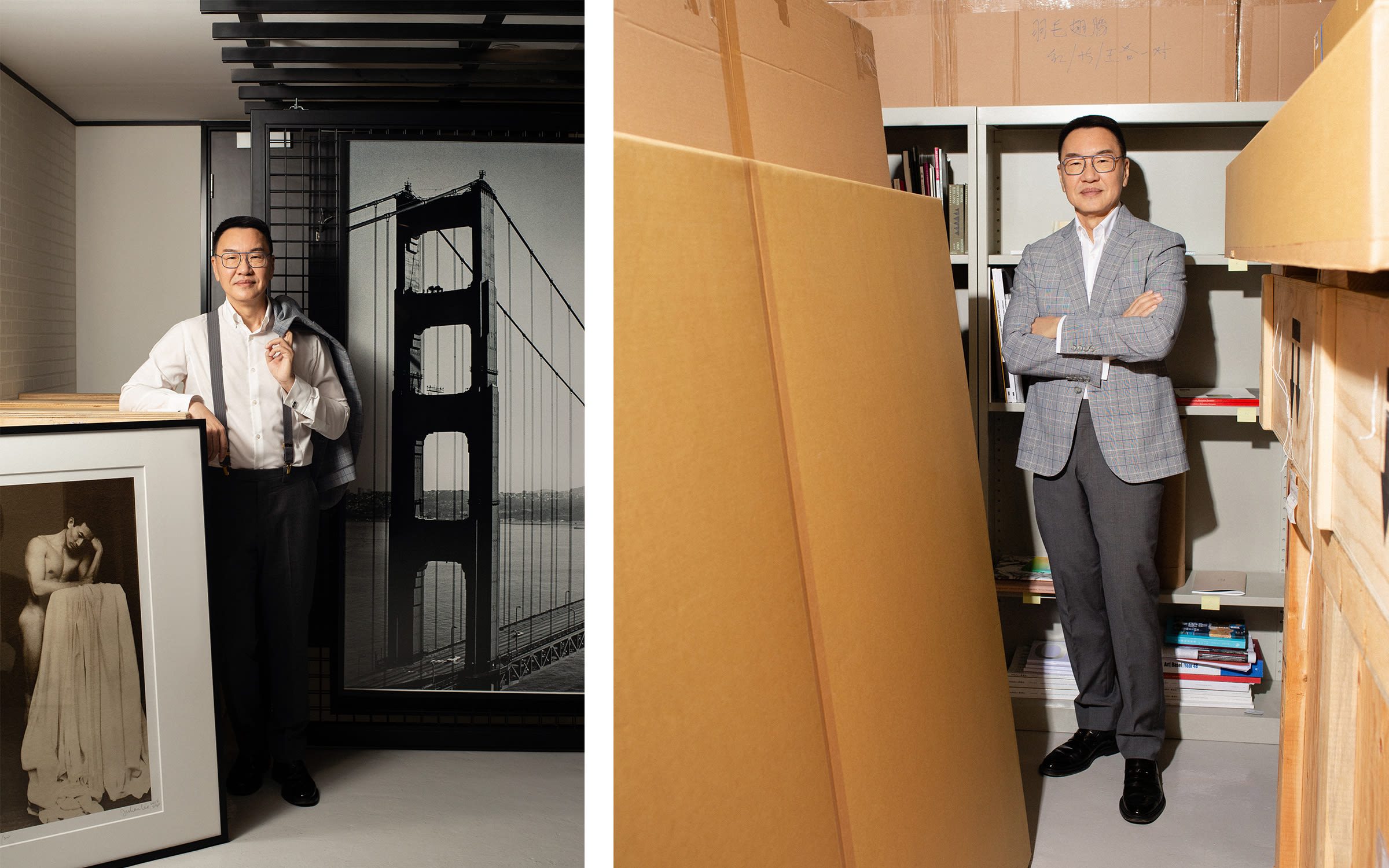

Why I Collect: Patrick Sun

Meet the Hong Kong collector supporting queer Asian art with pride

Log in and subscribe to receive Art Basel Stories directly in your inbox.

Meet the Hong Kong collector supporting queer Asian art with pride

Log in and subscribe to receive Art Basel Stories directly in your inbox.