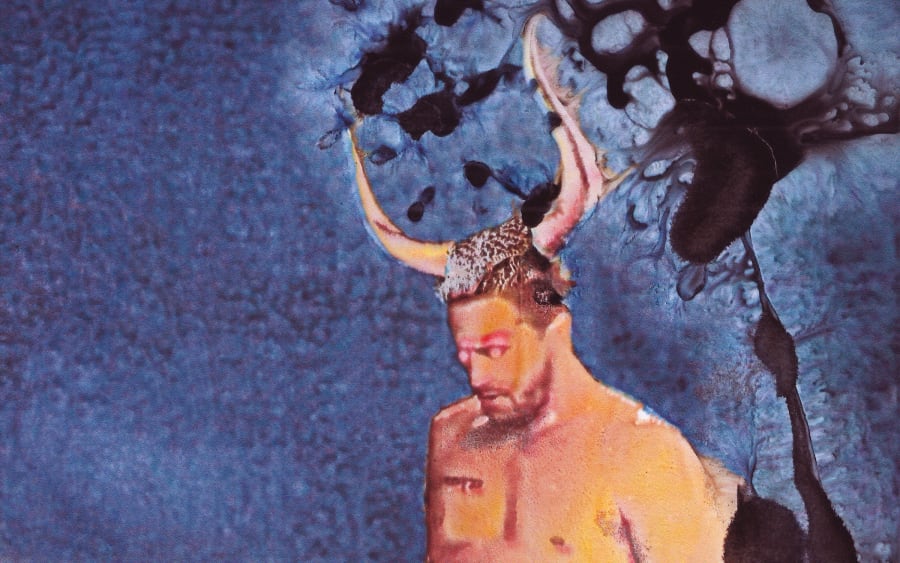

Arms raised and heads thrown back, three brown-skinned female bodies seem to merge into one. They dance in a trance, united, free, and powerful: they are witches. In 2019, the artist Dalila Dalléas Bouzar devoted a series to this figure of anarchy, who embodies the dark side of the supernatural. The witch is pictured in a state of metamorphosis – she is a possessor of societyʼs unspoken truths. On November 16, the Algerian-French artistʼs canvas Witches #5 will appear as part of the contemporary selection in the exhibition ʻWitches (1860-1920): Fantasies, Knowledge, Freedomʼ, presented at the Musée de Pont-Aven in partnership with the Musée dʼOrsay. The show traces the evolution of a female archetype that is at once rebellious and repressed, embodying the contradictions of modernity.

During a tragic period in Renaissance Europe, scores of women were accused of witchcraft, tens of thousands hanged or burned. The modern myth of the witch that inspire todayʼs artists only began to take shape however during the second half of the 19th century. In 1862, the historian Jules Michelet published his essay La Sorcière (The Witch), which helped establish her as a figure of (immense if ambiguous) power.

The witch was presented as a free and sensual woman associated with creation, nature, and an escape from civilization, defying the established powers of religion and patriarchy. She inspired a feminist awakening , as well as explosion of occultism and mysticism, which formed in reaction against the Industrial Revolution, the development of the sciences, and the increased exploitation of earthʼs natural resources.

In this era of scientific and technical progress, the figure was gradually less aestheticized and came to embody a more disturbing presence, fascinating and frightening at the same time – by turns madwoman, healer, seductress, rebel.

The exhibition at the Musée de Pont-Aven, which brings together various art forms, gives pride of place to the dark side of Romanticism, featuring the English Pre-Raphaelites Aubrey Beardsley, Edward Burne-Jones, and Julia Margaret Cameron, as well as the French Symbolists Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon. A common thread unites the works: the witch hunt. In his eponymous 1860 painting, Edward Burne-Jones depicts Sidonia von Bork as she is thrown onto the stake in 1620, while Eugène Grassetʼs series of drawings, The Legend of Joan of Arc: Joan at the Stake (1893), commemorates the brutal 1431 execution of the woman who was called a witch who became a martyr-saint.

Recent exhibitions have revived the memory of another persecuted figure: Tituba. This enslaved Indigenous woman was accused of witchcraft in 1692 during the Salem witch trials in the United States. The late Guadeloupean writer Maryse Condé, who died last year penned the 1986 cult classic I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem. Last winter, this novel became the foundation for the group exhibition ʻTituba, Who Will Protect Us?ʼ at the Palais de Tokyo in 2024-25. In the show that explored the role of myths, ancestors, and the invisible, Tituba was invoked as a protective presence. The assembled works reflected the Caribbean and African diasporic journeys of young artists like Rhea Dillon and Inès Di Folco.

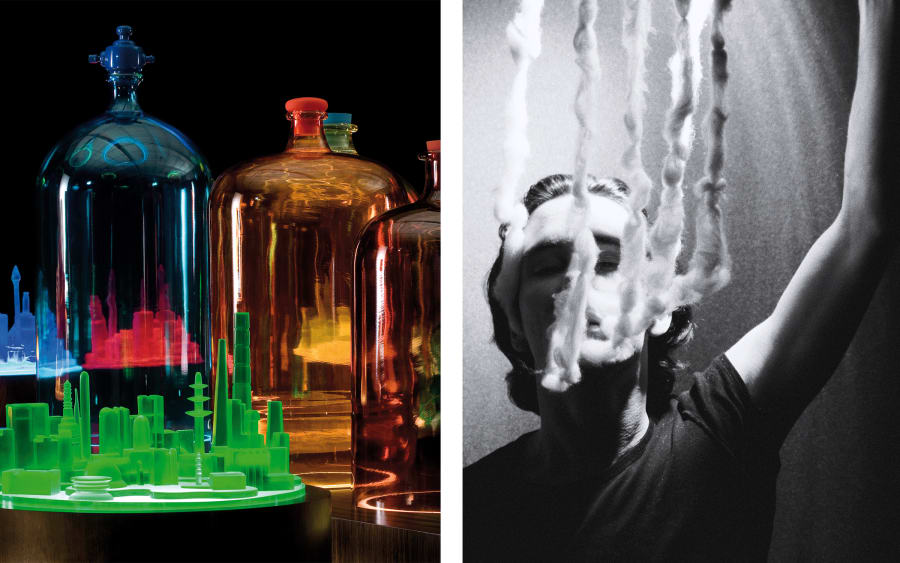

Today, the witch has become an icon of the struggle against patriarchal, Western, and rationalist thinking. At the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022 several historical sections were dedicated to still under-recognized protagonists. One of these capsules, titled ʻThe Witch's Cradleʼ, brought together women artists linked to Surrealism. The title came from an unfinished 1944 experimental, silent short film by the American director of Ukrainian origin Maya Deren (1917-1961) – a work that is said to have inspired David Lynch. With a haunted atmosphere and a spidery mise-en-scène, the film explores the power of magical objects. The two actors, Marcel Duchamp and Pajorita Matta, navigate a setting populated with occult and ritualistic symbols, including a pentagram and a human heart.

Currently being rediscovered by a new generation, Swiss artist Doris Stauffer (1934-2017) was a militant proponent of sorcery. A polymath and major figure in 1970s feminist activism, she was co-founder of the experimental Zurich art school F+F, where she organized women-only witchcraft courses. Apprentice witches learned, among other things, to transform their social situations into works of art through body photography, writing fictional biographies, and organizing public actions. In 2019, the Swiss Cultural Centre in Paris devoted a retrospective to her titled ʻDoris Stauffer: I Can Make a Lion Disappearʼ.

Three years later, the Centre Pompidou-Metz honored one of her compatriots. ʻThe Sentimental Museum of Eva Aeppliʼ was the first retrospective in France dedicated to the self-taught artist who took a fiercely independent path. Settled in Paris in the 1950s, Eva Aeppli (1925-2015) frequented the cityʼs avant-garde scene; she was close to Daniel Spoerri, Niki de Saint Phalle, Pontus Hultén, and she married Jean Tinguely in 1951. Wary of artistic fashions, the artist – whose business cards read ʻBreeder of Witchesʼ or ʻTamer of Vampiresʼ –positioned herself against the dominant aesthetics of her time, creating, from the 1960s onwards, life-size textile sculptures that were both mournful and poignant.

Another figure emerged simultaneously in Western visual culture. The 19th century not only created abundant images of witches but also spiritualist superstitions and otherstrange manifestations. Ghosts, specters, spirits, and all manner of hauntings had a similar revival to witches. From fall this year, Kunstmuseum Baselʼs exhibition ʻGhosts: Visualizing the Supernaturalʼ summoned apparitions of all kinds. Beginning with gothic tales from the Victorian era and the first Pictorialist photographs of the 1930s, the show explores more recent readings of phantoms and shadowy presenecs. The diversity of emotional registers reflects the ubiquity of this supernatural figure. A spirit gently mocks the artist himself in Mike Kelleyʼs series ʻEctoplasm Photographsʼ (1978-2009). Whereas Ryan Ganderʼs Tell My Mother Not to Worry (II) (2012) evokes the secret world of childhood through the sculptural transposition of his daughterʼs games of hiding under a white sheet.

If our era of technological upheaval and political tensions once again invokes dark, invisible forces, now – both good and evil but always irreverent –witches and specters emerge from oblivion to haunt our museum walls.

‘Sorcières (1860-1920) : fantasmes, savoirs, liberté’

Musée de Pont-Aven

Until November 16, 2025

‘Ghosts. Visualizing the Supernatural’

Kunstmuseum Basel

Until March 8, 2026

Ingrid Luquet-Gad is an art critic and PhD candidate based in Paris. She teaches art philosophy at Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne.

English translation: Art Basel.

Caption for header image: The Haunted Lane, ca. 1875. London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company © Denis Pellerin

Published on October 31, 2025.