In collaboration with Centre Pompidou

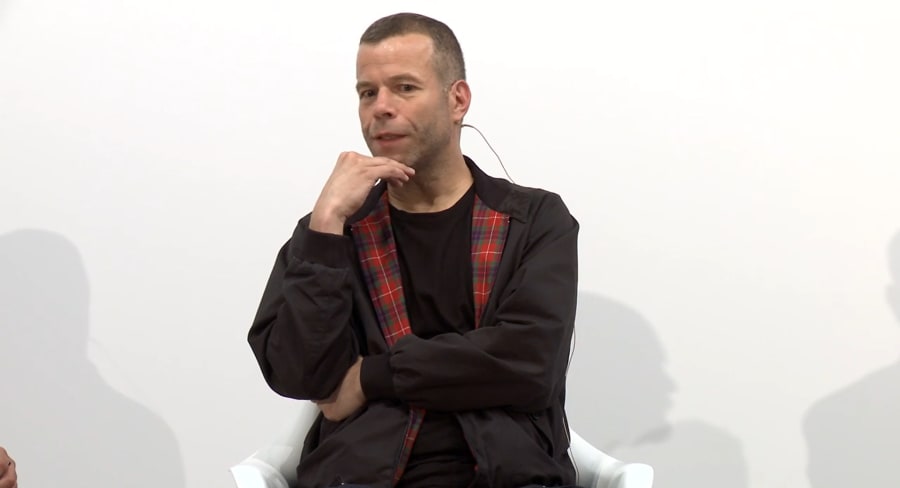

Leaning on the rail of the bar Le Central, overlooking the vast Forum of the Centre Pompidou one late afternoon, German artist Wolfgang Tillmans (b. 1968) takes photographs of the space – as if time were of the essence. As the iconic institution is gradually closing its public spaces ahead of its upcoming transformation, he has been invited to devise its final exhibition: a carte blanche extending across the entire 6,000 square meters of Level 2, which used to house the Public Information Library (Bpi), and which will relocate to Paris’s 12th arrondissement from September.

An unprecedented exhibition experience

‘A rare privilege,’ but also ‘a wild invitation, a real challenge,’ says the casually dressed artist, whose usual affability carries and air of gravity today. The clock is ticking, and the extraordinary model he built of the space in his Berlin studio is not quite enough to reassure him, since, meticulous as he is, preparation is key.

Stripped of its usual furniture (rows of standardized tables and chairs) and its towering shelves overflowing with books, the now-empty floor of the library offers a fully open space, recalling the origins of the Centre Pompidou itself. ‘I’ve spent the greater part of the time – actually, the entire first year – thinking about the architecture, the spatial layout, how to activate and use the space,’ says the artist, who, fully immersed in the project, frequently travels back and forth between Berlin and Paris.

He promises ‘a genuine experience,’ rather than a ‘retrospective’ – perhaps even ‘a foretaste of what the Centre Pompidou will be when it reopens in 2030,’ according to Laurent Le Bon, president of the Parisian institution.

Yet, while the architecture captivated the Remscheid native Tillmans from the outset of this unusual project, the function of the site also resonated with his practice. ‘I’ve always made books – artist books, books that I write with my images. There’s even a reprography section at the Bpi – and my initial encounter with photography happened through the lens of a photocopier.’ Indeed, his earliest works were grayscale laser photocopies, including the group ‘Approaches’ (1987–88). These were first shown in Hamburg, where the conscientious objector was completing his civil service. The process? Details from press images found in newspapers enlarged up to 400%, to the point of becoming graphic, abstract drawings as the print grid was magnified.

From rave culture to Europe

The first photograph he considers a work, Lacanau (self), dates from 1986. This nearly abstract self-portrait (a T-shirt, black shorts, knee, and sand seen from above) was a moment of self-discovery.

In the 1990s, his photographs of raves and subcultures across Europe brought him public recognition. Published in the British magazine i-D, they portrayed youth, Queer culture, and bodies through a documentary and inclusive lens. ‘Nightlife photography has always come from a sense of responsibility,’ Tillmans said in an interview in 2020. ‘I would like to document for the future that it existed, that it cannot be taken for granted, and that there are only very few places in the world where such an intense way of being together so fluidly and freely is possible.’ The artist remains the only person authorized to take photographs in Berghain, the legendary Berlin nightclub where freedom reigns supreme. However, he has not made use of this permission since 2012.

With his 2002 photograph The Cock (kiss) – taken at the eponymous London club night he frequented, which depicts a kiss between two men – he created an iconic image for Queer love with a self-evident tenderness and quietude. The image is neither staged nor militant, it simply captures a joyful moment of intimacy – nothing more. Art, after all, is a powerful language. ‘In the how, in the way of doing things, there’s already a seed for peace,’ Tillmans notes. ‘That doesn’t mean art always has to be peaceful; sometimes it must disrupt, shock.’ For him, ‘art always carries power, in good times as in bad. We may underestimate it – or overestimate it. Even those who are hostile to art, or claim not to care about it, know how powerful it can be. We see it clearly: Culture is always the first thing autocrats seek to control.’

In 2015, he photographed American rap star Frank Ocean, who openly addresses his homosexuality – a rare act in the world of hip-hop. The image, Frank, in the shower, also served as the cover for Ocean’s album Blonde. Coming out of the shower, the musician hides his face – leaving the interpretation open to the viewer. The subject’s vulnerability combined with the photograph’s immediacy swiftly elevated the work to iconic stature.

A year later, in 2016, as a true product of Postwar European history Tillmans became an outspoken advocate in the anti-Brexit campaign. Through the release of posters and T-shirts he passionately spoke out against Britain leaving the EU. Carrying slogans such as ‘What is lost is lost forever’ or ‘No man is an island. No country by itself’, alongside more direct messaging, they called on British voters to register and vote. A committed European, he lives between London and Berlin. He speaks German and English, and when in France, he often dips into French. ‘Just as a Texan and a Pennsylvanian feel American, a Spaniard and a Swede must be able to feel something for one another,’ says the artist, who studied in Bournemouth, UK, from 1990 to 1992, and traveled through Europe with an Interrail pass. He regrets that now the continent is so disparaged: ‘Many people in Europe – many citizens – still don’t realize that Europe should be their homeland of passion.’

A tireless archivist of the present

For Tillmans, paper is not just merely a support for writing or photography (a photosensitive surface) – it is a subject in its own right. It becomes sensual in Tillmans’s paper drop works, begun in 2001, where minimalism meets poetry. The entwined forms in Layers (2018) also echo the folds of stacked newspapers in Zeitungsstapel (1999), evoking his interest in accumulation and archiving – practices with which, he says, he has ‘a real affinity.’

This aspect of the library, far from incidental, is deeply embedded in his oeuvre. During the shoot, in the cluttered corridors of Level -1, Tillmans continually toys with a piece of string and a heart-shaped shipping label – found on-site – which he slips into the side pocket of his cargo pants, perhaps destined to be archived in the depths of his studio. The habit of gathering and accumulating little things without hierarchy speaks volumes about his relationship with the world around him.

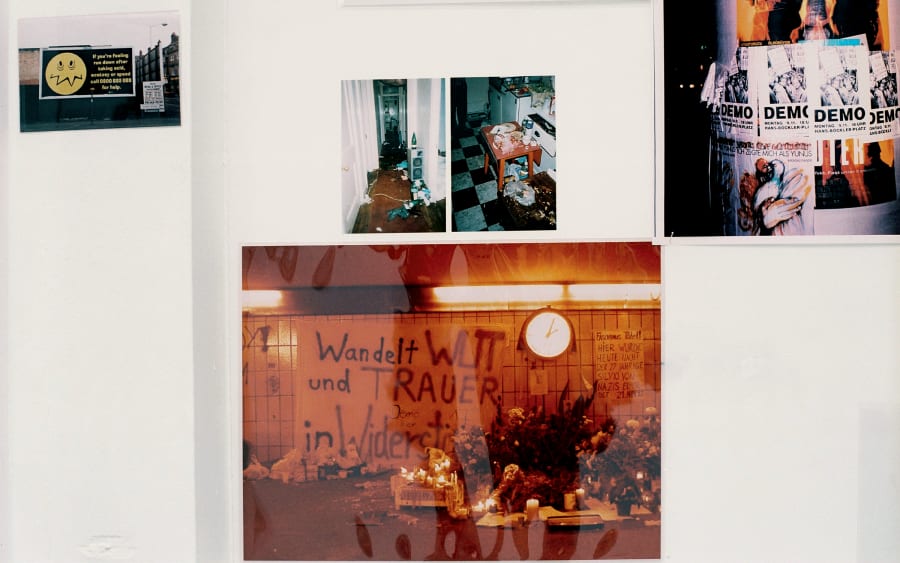

His mode of presenting works reflects this ethos. He shows his pictures both framed and unframed, in the latter case turning to delicate pins and clips or tape to fix the prints to the walls – an economy of means and an inclusive, democratic approach, which he developed at the beginning of his career. The prints are of different sizes, without hierarchy in the way they are shown or arranged. ‘What interests me,’ he notes, ‘is making images, making art – as a translation of the world I see.’ Eschewing conventional museum pathways, the artist purposefully gives no indication on the order in which the works should be seen; viewers are free to orient themselves. ‘I’ve often thought an artwork is just as interesting as the thoughts it provokes,’ says Tillmans, before adding: ‘It’s not just a spatial experience. It’s also my first major exhibition in Paris in 23 years. So visitors deserve a full picture of my work – which is definitely not presented chronologically.’

Tillmans’s practice far exceeds the boundaries of traditional photography: He creates lens-based and non-lens-based photographs, moving images, sound, and music, sometimes including text in his work. His main concern is to capture the surface of the world and transform it into a visual experience, engaging senses, emotions, and the intellect, and conveying the present in all its complexity and nuances – not as a mere representation, but as a process of observation, empathy, and construction. He offers images that function simultaneously as documents, inquiries, and emotional touchstones. Ultimately, this tireless archivist of the present continuously highlights the signs of our times, drawing on all available means: materials, intimacy, installations, politics, music… ‘I believe that through close observation, through striving to understand the nature of things, we can access a form of knowledge. We’re not merely passive in the flow of time – we can exercise some control, some influence,’ confides the artist, for whom the way we look at things is already political.

The title of the exhibition, ‘Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us’, thus resonates as a manifesto of sorts, intertwining his personal and political concerns. ‘The title dates from 2023,’ he says, ‘and it didn’t initially come to me in a political sense, but rather in relation to my personal life. As we grow older, we experience time: We see surprising things arriving, others we expected – or a mix of the two. I always try to honor that feeling in my work. I hadn’t foreseen that the title would take on a deeply political meaning – but perhaps I sensed it.’

Against AI, the truth of the analog

This same visceral attachment to democracy emerged in 2017 in his campaign against Germany’s far-right party AfD (Alternative für Deutschland). Minimalist design and direct address were his tools. He designed posters that struck a nerve, using text that was deliberately rooted in everyday language – and made them easily accessible to all by having them available for download from his website. By purchasing advertising space in 58 publications and distributing 750,000 free postcards, he sought to mobilize apolitical but open-minded voters to ‘prevent society from continuing to fall to pieces.’

But another threat looms over our democracies: artificial intelligence, which increasingly amplifies rumors and fake news propagated by the far right. ‘Artificial intelligence is a massive issue. It could cause real problems, weakening or even undermining democracies,’ Tillmans cautions. ‘The idea that photography might never again be proof of what was or what is – but become something else entirely – that really scares me,’ he continues. For 35 years, he has worked with analog processes, whether with film cameras, digital cameras, silver-palladium emulsions, or simply photosensitive paper coming out of dirty processing machines, as in his ‘Silver’ works. ‘You can trust my work: Everything you see in it came about because light hit a surface, a point. Not because I moved pixels afterwards.’

Why would an artist, a maker of images, need AI? ‘I find this world already so interesting, so fantastic, that I feel no attraction to digital processing, manipulation, or AI.’ He laments the boredom one feels in front of works created via such means, and states: ‘I’m grateful to still be interested in the world. To wake up in the morning and look at things with joy and curiosity. To still be drawn to portraiture, to people.’

This article is part of an editorial collaboration with the Centre Pompidou. Read the original article here.

Wolfgang Tillmans

‘Rien ne nous y préparait − Tout nous y préparait’

From June 13 until September 22, 2025

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Wolfgang Tillmans is represented by Galerie Chantal Crousel (Paris), Galerie Buchholz, Maureen Paley (London), and David Zwirner (New York, Hong Kong).

Pierre Malherbet is Editor in Chief at the Magazine, Centre Pompidou.

English translation: Centre Pompidou.

Caption for header image: Wolfgang Tillmans in the basement of the Centre Pompidou, just weeks before the move.

Photo © Pierre Malherbet

Published on June 10, 2025.