Every nightfall, the LED façade of M+ comes alive with the artist and filmmaker Yang Fudong’s new work Sparrow on the Sea (2024), a co-commission by M+ and Art Basel presented by UBS. The hour-long film tells the story of a life lived in Hong Kong’s city and countryside. The protagonist, Mr. Wu, revisits pivotal places from his life, with younger variations of himself appearing along the way. Rich with metaphors, Sparrow on the Sea is imbued with imagination and existential reflection. Kate Gu, M+’s Associate Curator, Digital Special Projects, spoke to Fudong about his powerfully poetic work.

‘I wanted to give this commissioned work a euphonious and visually metaphorical name. I want to convey that a little bird may have beautiful dreams and visions as it takes flight toward the boundless ocean. With the work’s English name, you can imagine a slow-motion shot of a bird flying over the sea. That little sparrow fills itself with great courage and is supported by the sea, the land, and everything else. I was wondering, when people grow older, will they still have the courage to do something that brings them happiness, something that they are longing for?

‘When I received the invitation from M+ to create this work, I was immediately compelled to shoot the film in Hong Kong. Many of the Hong Kong-based photographer Fan Ho’s works capture the light and shadows of the city. They are records of time and of its many textures. I have my interpretation, but I have also drawn on Ho’s works and aesthetic sensibility to nourish my creations.

‘At the beginning of Sparrow on the Sea, some fishermen find a suitcase by the sea but don’t know who its owner is. When the camera pans, the fishermen gaze into the lens to reflect their concern for the protagonist and to show that they witnessed everything that happened on the beach. The camera then turns to someone on the shore picking up the suitcase. This person is Mr. Wu, the film’s main character, and this is where the story begins.

‘Mr. Wu [wu means five in Chinese] could be a man in his fifties. He is played by three actors. Two of them portray different versions of a young Mr. Wu, with contrasting aspects that are like day and night, while the other plays an old Mr. Wu. The character has left traces of himself all over the city and at every stage of his life. These traces are woven together, which is why, in the same room, you’ll see a young Mr. Wu dancing, while another, older version of himself looks into a mirror, creating a sense of intertwining time and space.

‘At the beginning of the film, Mr. Wu picks up the suitcase and prepares to depart. This opening scene conveys the youthful desire to leave and pursue a beautiful life. In the decades that follow, Mr. Wu quietly comes and goes. Mr. Wu’s journey represents a cyclical reincarnation. Time flows slowly as we experience different life moments. The film, therefore, attempts to weave together time and memory, reassembling the confused and ambiguous episodes into a vivid journal of life.

‘The film ends with an octopus sliding out of a suitcase that is on the beach. The octopus evokes the imagery of some unknown creature in the vast ocean, and it’s unclear where the octopus goes and whether it heads into the sea. The final shot brings us back into the city, where a girl runs into the distance. This scene was filmed in Lan Kwai Fong and symbolizes reality.

‘Speaking of the narrative, I want to emphasize the idea of comprehension via sensing, which is the feeling of things that are hinted at but not explicitly explained. I sometimes think such ambiguity is the most accurate way to articulate feeling. From another perspective, “sensing” refers to how every individual experiences something. It is very abstract, and sometimes it is a bizarre connection or interpretation. The audience is, in fact, the film’s second director – when viewing the work, their life journey affects how they understand and interpret parts of the film.

‘When shooting Sparrow on the Sea, a psychological turning point took me back to the beginning of my artistic journey. My first film, An Estranged Paradise [2003], kept flashing inexplicably in my mind. I even borrowed a short swimming pool scene from it when editing the opening of Sparrow on the Sea. I didn’t know anything when I filmed An Estranged Paradise, I just relied on my youth and moved ahead fearlessly.

‘I later realized that many aspects of my daily life, including my creations, were inspired by An Estranged Paradise. Now, I’m going back to the starting point to digest the revelations brought by time. Should I go out into the sea or continue flying over the ocean? Instead of needing self-driven motivation, I opt to do things with a greater sense of ease. In a sense, flying across the vast ocean is not necessarily the absolute goal, but having the courage to do so may bring you happiness.

‘Sparrow on the Sea brings together various elements from other works of mine. For example, the man in the robe gestures not only to my memories of old Hong Kong kung fu movies but the character also appears in No Snow on the Broken Bridge [2006]. In addition, the film features the type of suitcase seen in Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest [2003–2007]. The ocean scenes recall The Light That I Feel [2014], shot in Norway.

‘This film was perhaps my first time really getting close to Hong Kong, observing it, and being near it. Hong Kong feels so big to me, not geographically but in terms of its richness and diversity. There are modern and old buildings, and there are natural landscapes. Such abundance enables me to experience a Hong Kong that is very different from the one I imagined or saw in movies. It gives me a sense of estrangement in my closeness.

‘Many things in daily life make me wonder if humans should be more like sparrows. Sparrows do not have many big concerns. Rather, they treasure their own lives. For example, we can spend our days catching up with friends and chatting over meals. That sort of life is real and truly present. We do not have to chase after seemingly grand aspirations that are difficult to reach, and we do not need to pursue an impractical life. Nowadays, many people will spend their entire lives desperately working and earning money. They work hard and are diligent, but it’s impossible to tell if this type of harvest is good or bad. Even if we earn very little money, we can still be content if we share a happy and peaceful life with those we love. Our understanding of life may change significantly with age.’

Yang Fudong’s Sparrow on the Sea (2024) was co-commissioned by M+ and Art Basel and presented by UBS. It will be screened on the M+ Facade through July 14, 2024 between 7pm and 9:15pm.

This article is from a conversation between Kate Gu, M+’s Associate Curator, Digital Special Projects, and the Beijing-born, Shanghai-based artist Yang Fudong. The full text version is available on the M+ Magazine. It was translated from Chinese to English by Cecilia Kwan and edited by Dorothy So, with English editorial support from Ulanda Blair, M+’s Curator, Moving Image.

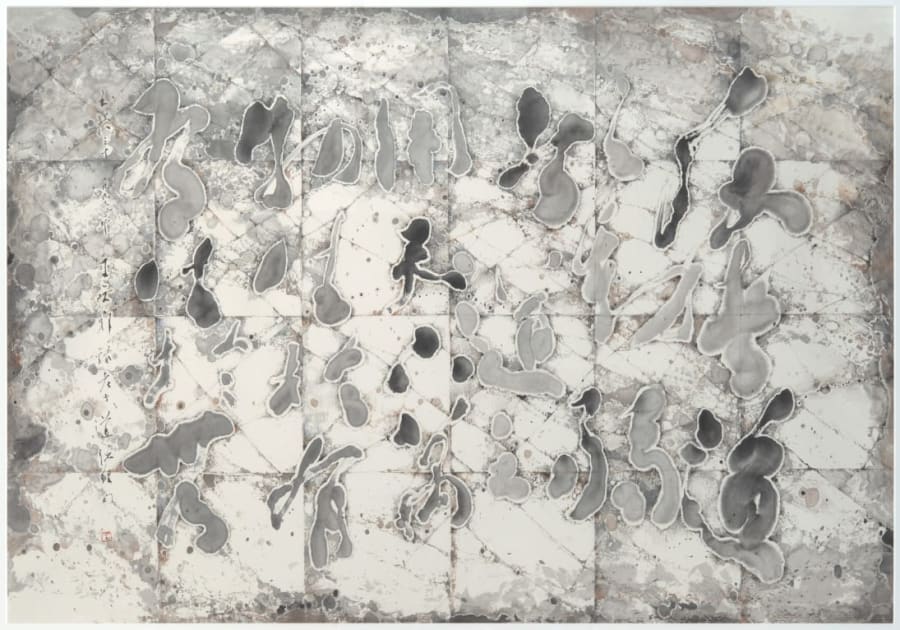

All images are from Yang Fudong, Sparrow on the Sea, 2024. Co-commissioned by M+ and Art Basel, presented by UBS, 2024. © Yang Fudong. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

Published on April 25, 2024.