In collaboration with Numéro art

Arthur Jafa occupies a prominent place in ‘Corps et âmes’, the new exhibition at the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection. The Los Angeles-based photographer and video artist presents three of his greatest films, including Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016), a vibrant homage to African American culture, acclaimed by critics and the public alike. The exhibition offers an opportunity to dive into the universe of this visual alchemist, who is capable of transforming pop references and archival images into powerful new meditations.

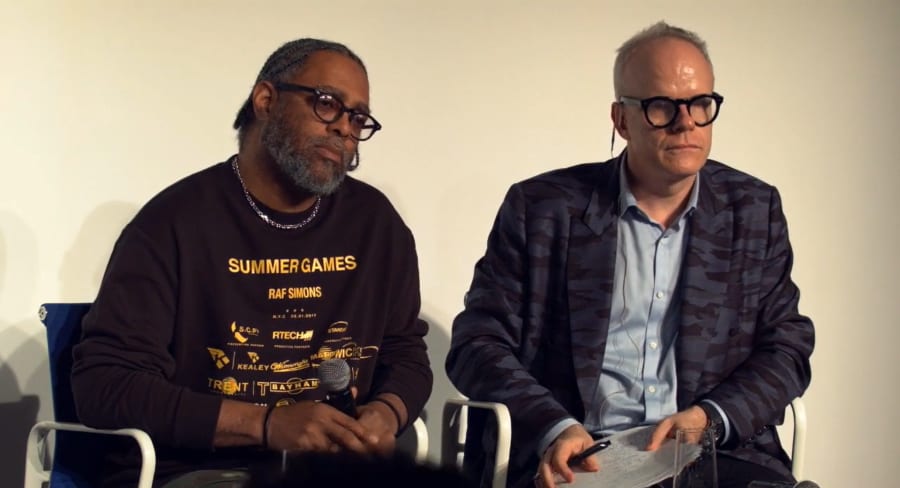

Cyrus Goberville: Black music has always played a key role in your work. How would you define it?

I believe it’s an integral part of the opposition between African ways of seeing the world and the Western understanding of time and space. Black music was the dominant cultural form of the 20th century. If you look at the reach of Black music, it’s not just Black folks who like Black music – that’s the thing. Black music is a product of the West. When you say Black music, everybody understands that it grew out of or evolved from traditional African music. But at the same time, I could mention 1,000 things that don’t sound like anything you’ve ever heard in traditional African music. Even when you say Black music, would you ever confuse Billie Holiday with Jimi Hendrix, or Jimi Hendrix with John Coltrane, or John Coltrane with Jay-Z? There are a zillion things that fit under this umbrella we call Black music. So, trying to understand Black music is just another form of trying to understand Blackness. Because it is not the only, but certainly the most prominent, expression of Black people’s existential experiences in the West.

How would you describe the complex relationship between your work and music?

Sometimes I have a slightly ambivalent relationship to music in my work, because it feels like the music is so powerful. It’s almost like you could literally just put the music over anything and it would be interesting. When people find an artifact and don’t know how old it is, they can carbon date it. I feel that putting music alongside visual stuff is a weird kind of carbon dating. I hate to use the word ‘authenticity’, but the power and depth of what’s happening on the visual side is marked by how that music is tracked alongside it.

You worked with Stanley Kubrick on his last movie Eyes Wide Shut [1999]. Was the use of music in your work in any way influenced by Kubrick’s soundtracks?

The monolith scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey [1968] is maybe the earliest instance I can think of where a filmmaker used classical music to accompany images. It’s a great archive of the difference between sound and image. There’s always a satirical edge with Kubrick: The music is outside of the image you’re looking at. In his films, like A Clockwork Orange [1972], or even Barry Lyndon [1975], where the music is of the period, the way the soundtrack works in relationship to the narrative is super sarcastic. It’s also true of Full Metal Jacket [1987], where in a very strange way you can’t remember the music at all; the only thing I remember is the soldiers singing, and when they sing the Mickey Mouse song, I know there must be music, but it almost feels like Robert Bresson, where music is absent.

Like the scene at the Gare de Lyon in Bresson’s Pickpocket [1959] which is entirely played out to the sound of footsteps.

Yes, that’s basically all you hear. It’s just those small ‘details’ of sound that make it work. It’s funny, I identify myself more with Bresson, even though in my videos I use music in a very emotional way, to create an atmosphere. But I don’t like that in cinema so much – the whole idea of music telling you how to think from moment to moment. Kubrick doesn’t do that. His use of music is really different, it almost takes on a creative role, casting a particular light on what we see. With him it’s very rare to see the music underlining the character’s emotions in any literal way, versus Scorsese, say, who uses music in a much more embedded way. If you think of Mean Streets [1973] or Taxi Driver [1976], the music is atmospheric more than anything.

Talking of Taxi Driver, in 2024 you showed the ambitious ***** (which you pronounce Redacted), a remake of one of the final scenes in Scorsese’s movie, where Travis Bickle, played by Robert De Niro, shoots people in an East Village brothel in New York to save Iris, the Jodie Foster character. In the original movie, the pimp Sport, played by Harvey Keitel, is white. When you discovered that the film’s screenwriter, Paul Schrader, had intended Sport to be African American, you decided to ‘restore’ the movie by introducing Black actors, alongside De Niro and Foster.

Exactly – a switching of the colors. I’ve definitely had friends of mine, Black folks, be like, ‘Why would you want to make the film so the good people are getting killed?’ My reply is that, first of all, I was just trying to make the film be true to itself and not be this confusing or contradictory artifact – to make it say what it believes, even if that’s fucked up. You can see it for what it is, rather than being subjected to these strategies that are basically about destabilizing your understanding of what you’re looking at. This sort of intervention is called détournement in French. I wanted to correct the film, or pull certain parts out to reveal its true nature.

I’ve been obsessed with Stevie Wonder’s music since I saw *****! Why did you use his song ‘As’ (1976), which is so joyful, when the pimp is in the street, just before something so dramatic is going to happen?

In 1976, everybody was listening to Stevie Wonder’s album Songs in the Key of Life [1976]. I remember that period well – it was all that my family listened to for two whole years, it dominated everything at home! At the end of the day, I think that the song that feels most emblematic of the whole record is ‘As’. It’s pretty apocalyptic in the biblical sense. Using it in ***** was just a way to say, ‘Hey, look, this pimp, you reckon you know what’s going on in his head, but you don’t know what’s going on in Black people’s heads.’ It’s also accurate for the period, because both Taxi Driver and Songs in the Key of Life were released in 1976, even though Wonder had been recording it for several years before.

Do you listen to new music?

I’m curious about anything. For years, I’ve been interested in Future. Like somebody said, he may not be the biggest rapper, but he’s more influential than Jay-Z.

Do you still own a lot of records?

Yes. There are some I haven’t listened to for 30 years, because I want to write about that period in my life, and I know that if I keep them to one side, when I play them they’ll instantly take me right back there. If you play the same music every day, you lose that. There’s a record by Stevie Wonder called Fulfillingness’ First Finale [1974]. My dad played it every morning before we went to school. So I don’t want to listen to it until I’m ready to write about that time. I’m literally avoiding it, because I know that if I listen to it, even just once or twice, even accidentally, it will take me straight back to that period.

This article is part of an editorial collaboration with the Numéro art. Read the original article here.

Arthur Jafa is represented by Gladstone Gallery (New York, Brussels, Rome, Seoul) and Sprüth Magers (Berlin, London, Los Angeles, New York).

Cyrus Goberville is in charge of cultural programming at the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris.

Arthur Jafa

Until August 25, 2025

Bourse de Commerce - Pinault Collection, Paris

English translation: Art Basel.

Caption for header image: Installation view of Arthur Jafa's Love is the Message, the Message is Death, 2016, in 'Corps et âmes' at Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, 2025. Pinault Collection © Arthur Jafa. Photo: Florent Michel / Pinault Collection.

Published on June 12, 2025.