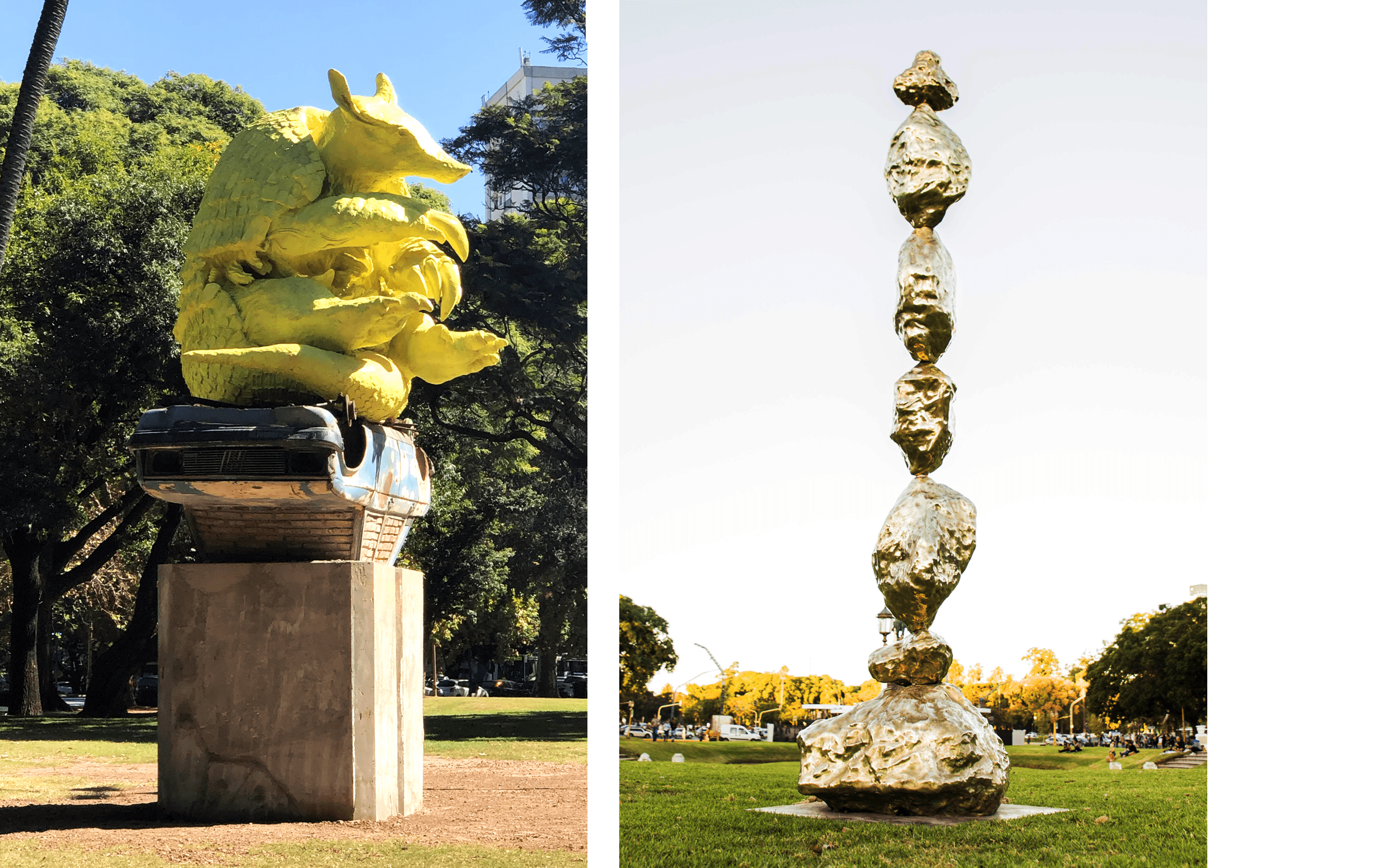

Going public: Three Argentine artists on the risks and rewards of showing art in unexpected places

Marie Orensanz, Luna Paiva, and Mariana Telleria discuss their installations in a city park for the Semana del Arte in Buenos Aires

Log in and subscribe to receive Art Basel Stories directly in your inbox.

Component not found for QTS CMS module.

Either mapping is wrong or this module has no Frontend component yet.

Either mapping is wrong or this module has no Frontend component yet.