When we discuss the art market, we sometimes forget those at its core: the artists. Be they sculptors from Ancient Egypt or Gen Z abstract painters, their work is why the art market exists, and how it generated an estimated USD 57.5 billion in 2024 alone, according to The Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report. Sales by commercial galleries and dealers account for 60% of that figure, a finding that underscores the vital role commercial galleries play in this complex ecosystem. Gallery representation can therefore be crucial in securing an artist’s income, visibility – and, often, their legacy too. But artists by far outnumber galleries, and getting gallery representation can be an arduous path. So what do art dealers typically consider when they are expanding their roster?

Having a unique, distinctive, and meaningful voice is key. ‘I always want to mount exhibitions with artists who are making the most important and radical art,’ says Sadie Coles, a leading figure in contemporary art and founder of her namesake gallery in London. Her ambition is noticeable in the gallery’s eclectic yet laser-sharp programming, which includes conceptual tricksters such as Darren Bader and Richard Prince, as well as skilled figurative painters like Isabella Ducrot and Georgia Gardner Gray.

Stefan Benchoam, who runs Proyectos Ultravioleta in Guatemala City, echoes Coles’s sentiment about how he chooses to work with artists. ‘We think less about the market implications, and more about that artist’s ability to push and expand the canon,’ says the gallerist, who represents some of his region’s most esteemed practitioners, including Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa, Vivian Suter, Edgar Calel, and Regina José Galindo.

Coles, who started her business in 1997, insists that expanding one’s roster is key to staying up-to-date. She notes that four of the most recent additions to her program – Karimah Ashadu, Meriem Bennani, Diego Marcon, and Arthur Jafa – all work with film and video. ‘That is in part because I think so much work being made with moving image actually represents our time so brilliantly,’ she adds.

Making innovative work is only one part of the equation – but if your art isn’t seen, then nobody can notice it. Therefore, finding ways to show is critical. That doesn’t necessarily mean exhibiting in a conventional environment. As Yasmil Raymond, a veteran curator and educator who oversees Art Basel Miami Beach’s Meridians sector, says, ‘The white cube is overrated. If you are making work and you are ready to show it, then nothing should stop you. Show it like Thomas Hirschhorn did, on top of car windows or on sidewalks. Rirkrit Tiravanija was doing shows in trucks when he was working as a mover to stay afloat. It’s about having imagination and a sense of humor.’

One solution can be to take matters into your own hands and create the environment to exhibit your art yourself. Many artists choose to run their own spaces to show their and their friends’ work – sometimes becoming gallerists in the process. Such was the trajectory of Benchoam, who explains that his desire to show his own art was the initial reason for him and his associates to co-found Proyectos Ultravioleta. For a gallerist, experience of what it means to be a practicing artist can also become a competitive advantage. Berlin-based artist Nuri Koerfer – who is best-known for her colorful furniture sprouting animal heads – started working with her primary gallery, Lars Friedrich, in part, because ‘Lars started off as an artist, which created a proximity when we first started talking,’ she says.

In an industry where traditional B2B dynamics sometimes feel intimidating, fostering such personal connections can be decisive. Koerfer didn’t only have artistic affinities with Friedrich, she was also close to several of his artists before she started working with him. Galleries are often also communities. Coles founded hers at the behest of Sarah Lucas and John Currin, both known for their genre-defying and sometimes controversial work; almost 30 years later, she still represents them. ‘A relationship with an artist always starts with friendships or long conversations,’ says Benchoam. ‘It’s a very organic process, without a specific formula.’

These relationships can often start early on in an artist’s career – typically at art school. There are hundreds of institutions across the world offering an arts education, but few are as prestigious as the Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, where Raymond was rector between 2020 and 2024. (She was also Director of Portikus, an associated kunsthalle, for the same period.) Städelschule is a particularly sought-after school, due in large part to the reputation – and influence – of its alumni and faculty. The list of its current and past members reads like a who’s who of contemporary art: Haegue Yang, Amy Sillman, and Willem de Rooij all taught there. Former students include Anne Imhof, Danh Vo, and Simon Denny. Gallerists from across the world regularly visit its famed ‘Rundgang’, a yearly show of student work, and faculty members may introduce their students to the galleries they themselves work with.

But higher education at a Western European university is out of reach for many. In regions of the world that aren’t as connected to the globalized art world – and consequently, where access to commercial and institutional recognition can be more challenging – being part of a strong local network is even more significant. There, too, galleries can play a central role. ‘We’re naturally drawn to creating spaces for the community – for the artists of course, but also for a wider audience,’ says Benchoam. As a gallery active on the global art fair circuit, Proyectos Ultravioleta has become a primary interlocutor for those interested in work by artists from the region. ‘Oftentimes, curators or staff from biennials and big museums are coming to us as the first point of contact in Guatemala. We have materials ready for them to get the best sense of our rich local ecosystem and culture as a whole,’ he explains. During the pandemic, the gallery also initiated a program of micro-grants for artists, and is now getting ready to launch an editions arm, called Gentle Press, to support creatives from the region (regardless of whether the gallery represents them or not) as well as social causes its founders care about.

This diversification shows that in today’s hyper-connected world, galleries also need to find new ways to service artists. ‘The art world is now enormous, and as such, gallery representation has become much more multilayered,’ says Coles. Beyond showing and selling an artist’s work, representation ‘can go from running somebody’s archive, to providing and making content for someone’s digital presence, to straightforward production, which can scale from small to very big quite rapidly,’ she explains.

However, whatever else, when it comes to securing gallery representation, all interviewees agree: What matters most is developing a rich body of work – and that can take time. ‘A career lasts a long time,’ says Raymond, ‘there might be periods when you don’t exhibit, or struggle to create something meaningful. But that’s important. Love that process.’ Koerfer, who points out that she only started working with a gallery just before turning 40, advises to ‘concentrate on your work and ask yourself: how do I build an artistic practice and a good body of work?’ Ultimately, a skilled gallerist will notice when they’re in front of work with real strength, whether it’s by a 22- or a 75-year-old. As Coles puts it: ‘I seek out artists who can translate the human experience in a different way: pathfinders, shamans, dreamers, wizards, prophets.’

Karim Crippa is the Head of Communications of Art Basel Paris and Senior Editor at Art Basel.

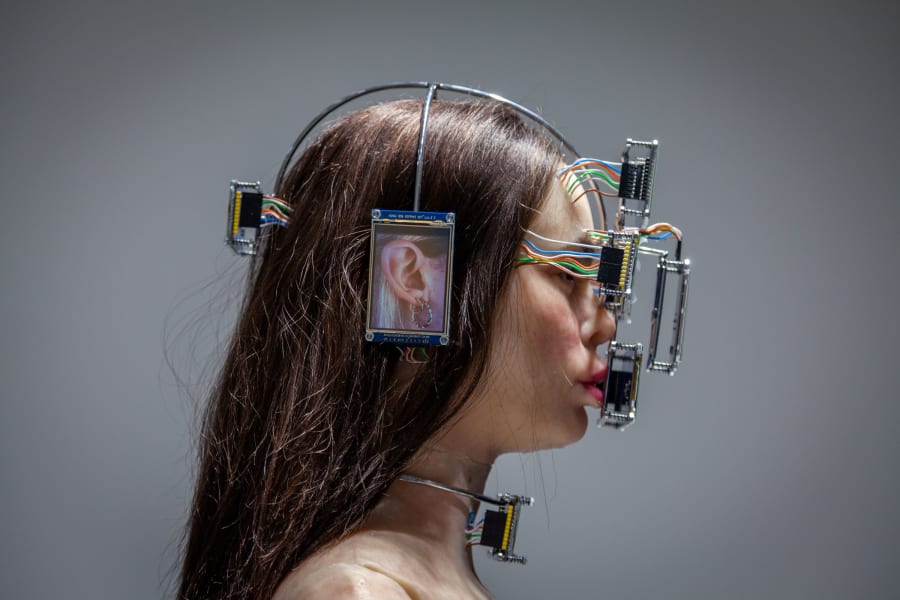

Top image: A visitor at Art Basel in Basel 2025.